PHOTOGRAPHS ALBUM

The double Theodosian Walls (Greek: teichos Theodosiakon), located about 2 km to the west of the old Constantinian Wall, were erected during the reign of Emperor Theodosius II (r. 408 - 450), after whom they were named. The work was carried out in two phases, with the first phase erected during Theodosius' minority under the direction of Anthemius, the praetorian prefect of the East, and was finished in 413 according to a law in the Codex Theodosianus.

An inscription discovered in 1993 however records that the work lasted for nine years, indicating that construction had already begun ca. 404 - 405, in the reign of Emperor Arcadius (r. 395 - 408). This initial construction consisted of a single curtain wall with towers, which now forms the inner circuit of the Theodosian Walls. Both the Constantinian and the original Theodosian walls were severely damaged, however, in two earthquakes, on 25 September 437 and on 6 November 447. The latter was especially powerful, and destroyed large parts of the wall, including 57 towers.

Subsequent earthquakes, including another major one in January 448, compounded the damage. Theodosius II ordered the praetorian prefect Constantine to supervise the repairs, made all the more urgent as the city was threatened by the presence of Attila the Hun in the Balkans. Employing the city's "Circus factions" in the work, the walls were restored in a record 60 days, according to the Byzantine chroniclers and three inscriptions found in situ.

It is at this date that the majority of scholars believe the second, outer wall to have been added, as well as a wide moat opened in front of the walls, but the validity of this interpretation is questionable; the outer wall was possibly an integral part of the original fortification concept. Throughout their history, the walls were damaged by earthquakes and floods of the Lycus river. Repairs were undertaken on numerous occasions, as testified by the numerous inscriptions commemorating the emperors or their servants who undertook to restore them.

The responsibility for these repairs rested on an official variously known as the Domestic of the Walls or the Count of the Walls (Domestikos / Komēs tōn teicheōn), who employed the services of the city's populace in this task. After the Latin conquest of 1204, the walls fell increasingly into disrepair, and the revived post-1261 Byzantine state lacked the resources to maintain them, except in times of direct threat.

Course and topography

In their present state, the Theodosian Walls stretch for about 5.7 km from south to north, from the "Marble Tower" (Turkish: Mermer Kule), also known as the "Tower of Basil and Constantine" (Greek: Pyrgos Basileiou kai Kōnstantinou) on the Propontis coast to the area of the Palace of the Porphyrogenitus (Tr. Tekfur Sarayı) in the Blachernae quarter.

The outer wall and the moat terminate even earlier, at the height of the Gate of Adrianople. The section between the Blachernae and the Golden Horn does not survive, since the line of the walls was later brought forward to cover the suburb of Blachernae, and its original course is impossible to ascertain as it lies buried beneath the modern city.

From the Sea of Marmara, the wall turns sharply to the northeast, until it reaches the Golden Gate, at about 14 m above sea level. From there and until the Gate of Rhegion the wall follows a more or less straight line to the north, climbing the city's Seventh Hill. From there the wall turns sharply to the northeast, climbing up to the Gate of St. Romanus, located near the peak of the Seventh Hill at some 68 m above sea level.

From there the wall descends into the valley of the river Lycus, where it reaches its lowest point at 35 m above sea level. Climbing the slope of the Sixth Hill, the wall then rises up to the Gate of Charisius or Gate of Adrianople, at some 76 m height. From the Gate of Adrianople to the Blachernae, the walls fall to a level of some 60 m. From there the later walls of Blachernae project sharply to the west, reaching the coastal plain at the Golden Horn near the so-called Prisons of Anemas.

Construction

The Theodosian Walls consist of the main inner wall "great wall", separated from the lower outer wall (exō teichos or mikron teichos), "small wall" by a terrace, the peribolos. Between the outer wall and the moat (souda) there stretched an outer terrace, the parateichion, while a low breastwork crowned the moat's eastern escarpment. Access to both terraces was possible through posterns on the sides of the walls' towers.

The inner wall is a solid structure, 4.5 - 6 m thick and 12 m high. It is faced with carefully cut limestone blocks, while its core is filled with mortar made of lime and crushed bricks. Between seven and eleven bands of brick, ca. 40 cm thick, traverse the structure, not only as a form of decoration, but also strengthening the cohesion of the structure by bonding the stone façade with the mortar core, and increasing endurance to earthquakes. The wall was strengthened with 96 towers, mainly square but also a few octagonal ones, three hexagonal and a single pentagonal one.

They were 15 - 20 m tall and 10 - 12 m wide, and placed at irregular distances, according to the rise of the terrain: the intervals vary between 21 and 77 m, although most curtain wall sections easure between 40 to 60 meters. Each tower had a battlemented terrace on the top. Its interior was usually divided by a floor into two chambers, which did not communicate with each other. The lower chamber, which opened through the main wall to the city, was used for storage, while the upper one could be entered from the wall's walkway, and had windows for view and for firing projectiles.

Access to the wall was provided by large ramps along their side. The lower floor could also be accessed from the peribolos by small posterns. Generally speaking, most of the surviving towers of the main wall have been rebuilt either in Byzantine or in Ottoman times, and only the foundations of some are of original Theodosian construction. Furthermore, while until the Komnenian period the reconstructions largely remained true to the original model, later modifications ignored the windows and embrasures on the upper store and focused on the tower terrace as the sole fighting platform.

The outer wall was 2 m thick at its base, and featured arched chambers on the level of the peribolos, crowned with a battlemented walkway, reaching a height of 8.5 - 9 m. Access to the outer wall from the city was provided either through the main gates or through small posterns on the base of the inner wall's towers. The outer wall likewise had towers, situated approximately midway between the inner wall's towers, and acting in supporting role to them. They are spaced at 48 - 78 m, with an average distance of 50 - 66 m. Only 62 of the outer wall's towers survive.

With few exceptions, they are square or crescent-shaped, 12 - 14 m tall and 4 m wide. They featured a room with windows on the level of the peribolos, crowned by a battlemented terrace, while their lower portions were either solid or featured small posterns, which allowed access to the outer terrace. The outer wall was a formidable defensive edifice in its own right: in the sieges of 1422 and 1453, the Byzantines and their allies, being too few to hold both lines of wall, concentrated on the defence of the outer wall.

The moat was situated at a distance of about 20 m from the outer wall. The moat itself was over 20 m wide and as much as 10 m deep, featuring a 1.5 m tall crenellated wall on the inner side, serving as a first line of defence. Transverse walls cross the moat, tapering towards the top so as not to be used as bridges. Some of them have been shown to contain pipes carrying water into the city from the hill country to the city's north and west. Their role has therefore been interpreted as that of aqueducts for filling the moat and as dams dividing it into compartments and allowing the water to be retained over the course of the walls.

According to Alexander van Millingen, however, there is little direct evidence in the accounts of the city's sieges to suggest that the moat was ever actually flooded. In the sections north of the Gate of St. Romanus, the steepness of the slopes of the Lycus valley made the construction maintenance of the moat problematic; it is probable therefore that the moat ended at the Gate of St. Romanus, and did not resume until after the Gate of Adrianople.

The weakest section of the wall was the so-called Mesoteichion "Middle Wall". Modern scholars are not in agreement over the extent of this portion of the wall, which has been variously defined from as narrowly as the stretch between the Gate of St. Romanus and the Fifth Military Gate (A.M. Schneider) to as broad as from the Gate of Rhegion to the Fifth Military Gate (B. Tsangadas) or from the Gate of St. Romanus to the Gate of Adrianople (A. van Millingen).

Wall Gates

The wall contained nine main gates, which pierced both the inner and the outer walls, and a number of smaller posterns. The exact identification of several gates is a debatable, for a number of reasons. The Byzantine chroniclers provide more names than the number of the gates, the original Greek names fell mostly out of use during the Ottoman period, and literary and archaeological sources provide often contradictory information.

Only three gates, the Golden Gate, the Gate of Rhegion and the Gate of Charisius, can be established directly from the literary evidence. In the traditional nomenclature, established by Philipp Anton Dethier in 1873, the gates are distinguished into the "Public Gates" and the "Military Gates", which alternated over the course of the walls.

According to Dethier's theory, the former were given names and were open to civilian traffic, leading across the moat on bridges, while the latter were known by numbers, restricted to military use, and only led to the outer sections of the walls. Today however, this division is, if at all, retained only as a historiographical convention. First, there is sufficient reason to believe that several of the "Military Gates" were also used by civilian traffic.

In addition, a number of them have proper names, and the established sequence of numbering them, based on their perceived correspondence with the names of certain city quarters lying between the Constantinian and Theodosian walls which have numerical origins, has been shown to be erroneous: for instance, the Deuteron, the "Second" quarter, was not located in the southwest behind the Gate of the Deuteron or "Second Military Gate" as would be expected, but in the northwestern part of the city.

First Military Gate

First Military Gate, or Gate of Christ. The gate is a small postern, which lies at the first tower of the land walls, at the junction with the sea wall. It features a wreathed Chi-Rhō Christogram above it. It was known in late Ottoman times as the Tabak Kapı.

Xylokerkos Gate or Gate of Belgrade.

The Xylokerkos or Xerokerkos Gate, now known as the Belgrade Gate (Belgrat Kapısı), lies between towers 22 and 23. Alexander van Millingen identified it with the Second Military Gate, which however is located further north. Its name derives from the fact that it led to a wooden circus (amphitheatre) outside the walls. The gate complex is approximately 12 m wide and almost 20 m high, while the gate itself spans 5 m.

According to a story related by Niketas Choniates, in 1189 the gate was walled off by Emperor Isaac II Angelos, because according to a prophecy, it was this gate that Western Emperor Frederick Barbarossa would enter the city through. It was re-opened in 1346, but closed again before the siege of 1453 and remained closed until 1886, leading to its early Ottoman name, Kapalı Kapı "Closed Gate".

Second Military Gate

Second Military Gate, the greatest of the military gates. The gate is located between towers 30 and 31, little remains of the original gate, and the modern reconstruction may not be accurate. It is known today as Belgrade Gate (Belgrad Kapısı), after the Serbian artisans settled there by Sultan Suleyman the Magnificent after he conquered Belgrade in 1521.

Gate of the Spring

The Gate of the Spring or Pēgē Gate was named after a popular monastery outside the Walls, the Zōodochos Pēgē "Life-giving Spring" in the modern suburb of Balıklı. Its modern Turkish name, Gate of Selymbria (Tr. Silivri Kapısı), appeared in Byzantine sources shortly before 1453. It lies between the heptagonal towers 35 and 36, which were extensively rebuilt in later Byzantine times: its southern tower bears an inscription dated to 1439 commemorating repairs carried out under John VIII Palaiologos.

The gate arch was replaced in the Ottoman period. In addition, in 1998 a subterranean basement with 4th / 5th century reliefs and tombs was discovered underneath the gate. Van Millingen identifies this gate with the early Byzantine Gate of Melantias, but more recent scholars have proposed the identification of the latter with one of the gates of the city's original Constantinian Wall. It was through this gate that the forces of the Empire of Nicaea, under General Alexios Strategopoulos, entered and retook the city from the Latins on 25 July 1261.

Third Military Gate

The Third Military Gate, named after the quarter of the Triton "the Third" that lies behind it, is situated shortly after the Pege Gate, exactly before the C-shaped section of the walls known as the "Sigma", between towers 39 and 40. It has no Turkish name, and is of middle or late Byzantine construction. The corresponding gate in the outer wall was preserved until the early 20th century, but has since disappeared. It is very likely that this gate is to be identified with the Gate of Kalagros.

Gate of Rhegion

Modern Yeni Mevlevihane Kapısı, located between towers 50 and 51 is commonly referred to as the Gate of Rhegion in early modern texts, allegedly named after the suburb of Rhegion (modern Küçükçekmece), or as the Gate of Rhousios after the hippodrome faction of the Reds which was supposed to have taken part in its repair.

From Byzantine texts however it appears that the correct form is Gate of Rhesios, named according to the 10th-century Suda lexicon after an ancient general of Greek Byzantium. A.M. Schneider also identifies it with the Gate of Myriandr[i]on or Polyandrion "Place of Many Men", possibly a reference to its proximity to a cemetery. It is the best-preserved of the gates, and retains substantially unaltered from its original, 5th-century appearance.

Fourth Military Gate

The so-called Fourth Military Gate stands between towers 59 and 60, and is currently walled up. Recently, it has been suggested that this gate is actually the Gate of St. Romanus, but the evidence is uncertain.

Gate of St. Romanus

The Gate of St. Romanus was named so after a nearby church and lies between towers 65 and 66. It is known in Turkish as Topkapı, the "Cannon Gate", after the great Ottoman cannon, the "Basilic", that was placed opposite it during the 1453 siege. With a gatehouse of 26,5 m, it is the second-largest gate after the Golden Gate. It is here that Constantine XI Palaiologos, the last Byzantine emperor, was killed on 29 May 1453.

Fifth Military Gate

The Fifth Military Gate lies immediately to the north of the Lycus stream, between towers 77 and 78, and is named after the quarter of the Pempton "the Fifth" around the Lycus. It is heavily damaged, with extensive late Byzantine or Ottoman repairs evident. It is also identified with the Byzantine Gate of (the Church of) St. Kyriake, and called Sulukulekapı "Water-Tower Gate" or Hücum Kapısı ("Assault Gate") in Turkish, because there the decisive breakthrough was achieved on the morning of 29 May 1453. In the late 19th century, it appears as the Örülü kapı "Walled Gate". Some earlier scholars, like J.B. Bury and Kenneth Setton, identify this gate as the "Gate of St. Romanus" mentioned in the texts on the final siege and fall of the city.

Gate of Charisius

The Gate of Char[i]sius, named after the nearby early Byzantine monastery founded by a vir illustris of that name, was, after the Golden Gate, the second most important gate. In Turkish it is known as Edirnekapı "Adrianople Gate", and it is here where Mehmed II made his triumphal entry into the conquered city.

This gate stands on top of the sixth hill, which was the highest point of the old city at 77 meters. It has also been suggested as one of the gates to be identified with the Gate of Polyandrion or Myriandrion, because it led to a cemetery outside the Walls. The last Byzantine emperor, Constantine XI, established his command here in 1453.

Minor gates and posterns

Known posterns are the Yedikule Kapısı, a small postern after the Yedikule Fort (between towers 11 and 12), and the gates between towers 30/31, already walled up in Byzantine times, and 42/43, just north of the "Sigma". On the Yedikule Kapısı, opinions vary as to its origin: some scholars consider it to date already to Byzantine times, while others consider it an Ottoman addition.

Kerkoporta

According to the historian Doukas, on the morning of 29 May 1453, the small postern called Kerkoporta was left open by accident, allowing the first fifty or so Ottoman troops to enter the city. The Ottomans raised their banner atop the Inner Wall and opened fire on the Greek defenders of the peribolos below. This spread panic, beginning the rout of the defenders and leading to the fall of the city. In 1864, the remains of a postern located on the Outer Wall at the end of the Theodosian Walls, between tower 96 and the so-called Palace of the Porphyrogenitus, were discovered and identified with the Kerkoporta by the Greek scholar A.G. Paspates.

Later historians, like van Millingen and Steven Runciman have accepted this theory as well. However, excavations at the site have uncovered no evidence of a corresponding gate in the Inner Wall (now vanished) in that area, and it may be that Doukas' story is either invention or derived from an earlier legend concerning the Xylokerkos Gate, which several earlier scholars also equated with the Kerkoporta.

Later history

The Theodosian Walls were without a doubt among the most important defensive systems of Late Antiquity. Indeed, in the words of the Cambridge Ancient History, they were "perhaps the most successful and influential city walls ever built - they allowed the city and its emperors to survive and thrive for more than a millennium, against all strategic logic, on the edge of [an] extremely unstable and dangerous world...".

With the advent of siege cannons, however, the fortifications became obsolete, but their massive size still provided effective defence, as demonstrated during the Second Ottoman Siege in 1422. In the final siege, which led to the fall of the city to the Ottomans in 1453, the defenders, severely outnumbered, still managed to repeatedly counter Turkish attempts at undermining the walls, repulse several frontal attacks, and restore the damage from the siege cannons for almost two months.

Finally, on 29 May, the decisive attack was launched, and when the Genoese general Giovanni Giustiniani was wounded and withdrew, causing a panic among the defenders, the walls were taken. After the capture of the city, Mehmed had the walls repaired in short order among other massive public works projects, and they were kept in repair during the first centuries of Ottoman rule.

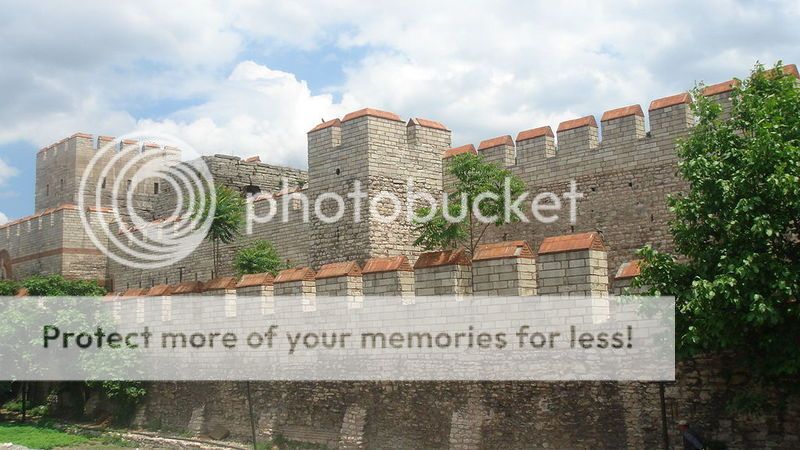

Restored section of the Theodosian Walls at the Selymbria Gate. The Outer Wall and the wall of the moat are visible, with a tower of the Inner Wall in the background.

Preservation and Restoration

Many sections were restored during the 1980s, with financial support from UNESCO, but the restoration programme has been criticised for focusing on superficial restoration and poor quality of work, which became apparent in recent earthquakes, as well as destroying historical evidence. Nonetheless, the restored sections give a fairly accurate image of the walls as they stood during Byzantine times. The wall runs through the suburbs of modern Istanbul, with a belt of parkland flanking their course. The walls are pierced at intervals by modern roads leading westwards out of the city.

This became apparent in the 1999 earthquakes, when the restored sections collapsed while the original structure underneath remained intact. The threat posed by urban pollution, and the lack of a comprehensive restoration effort, prompted the World Monuments Fund to include them on its 2008 Watch List of the 100 Most Endangered Sites in the world.

These scripts and photographs are registered under © Copyright 2017, respected writers and photographers from the internet. All Rights Reserved.

No comments:

Post a Comment