GPS : 41°00'26.0"N 28°58'49.0"E / 41.007222, 28.980278

PHOTOGRAPHS ALBUM

The palace was located between the ancient Hippodrome,Hagia Sophia and the Marmara Sea, behind the Blue Mosque today. The Great Palace was first built by Constantine in the 4th century , than used by later emperors until the 12th century. The Great Palace palace was abandoned during Latin Occupation between 1204-1261 when the emperors moved to the Blachernai Palaces (also known as Tekfur Palace).

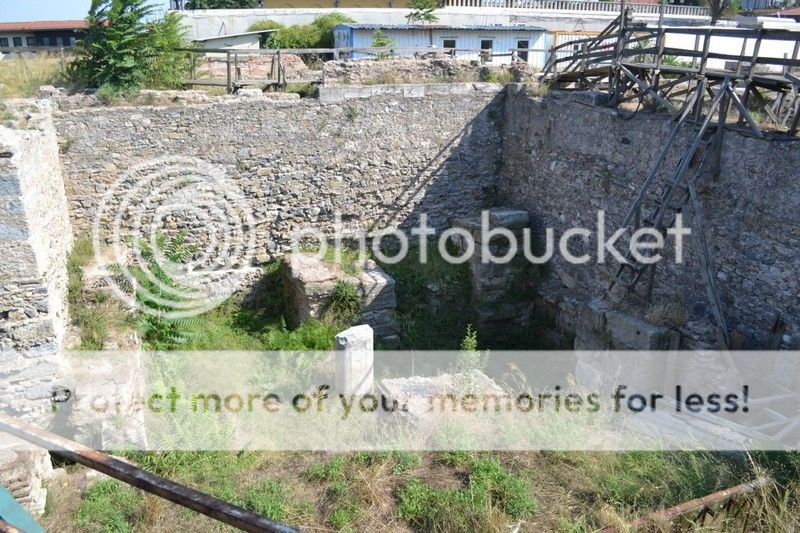

Ruins of the palace that was the seat of government for the eastern Roman and Byzantine empires for more than a millennium have been found beneath Istanbul's streets, according to Alpay Pasinli, director of the Istanbul Museum of Archaeology, who oversaw the excavations. Restoration work on the Four Seasons Hotel, originally an Ottoman prison, led to the discovery, which lies between the Byzantine church Ayia Sophia, now a museum, and the entrance to the Topkapı Palace of the Ottoman sultans.

Byzantine palace remains exposed at ground level include several collapsed columns, water conduits, and a wall, possibly part of a tomb, with frescoes of a cross motif in yellow, red, and green. The ground breaks away at one point to reveal a large subterranean chamber constructed of vaulted brick arches and domes supported by 16-foot-tall stone columns. The domes are about ten feet in diameter and five feet high.

A number of narrow tunnels lead from the chamber, but their extent has not been determined. Early speculation was that they might be the pitae, archives housing manuscripts and icons. The structure's exact age is unclear. Pasinli, who is not a Byzantinist, told Reuters it was of the fifth century, but in other reports it has been dated to the sixth or ninth century; Halil Ozek, another archaeologist involved in the excavations, told the New York Times that it was of ninth-century date.

Construction of the palace began under Constantine, who moved the capital of the Roman Empire to the city in A.D. 330. Expanded over a number of centuries, the palace included ceremonial halls, churches, and gardens on 100 acres of land extending from the Hippodrome, now Sultanahmet Square, to the Sea of Marmara. By the time Sultan Mehmet II captured Constantinople in 1453, it had fallen into disrepair and was largely abandoned.

The Ottomans sited their palace partly on the ruins of the old one, the rest of the Byzantine complex being buried beneath centuries of other buildings. The site's future is uncertain. Pasinli is no longer speaking to reporters after the Turkish press alleged that he was connected with artifact smuggling and that the palace discovery was a scam involving the hotel, which wanted to cash in on the find by converting part of the uncovered palace remains into a tourist bazaar.

None of these allegations is proven, but Pasinli is under investigation by the Ministry of Culture. Pasinli is on the Preservations Commission, which is charged with granting building permits for projects in areas of archaeological interest (the whole of Sultanahmet Square has been such an area since 1990). According to his detractors, Pasinli, who has powerful political, business, and union backers, has ensured passage of permit applications by the commission. One such application was for the restoration of the hotel.

What happened to the palace remains that must have been found during this work, which involved digging a large hole underneath the hotel, is unknown. The hotel, which also wanted to build on the site of the new discovery, paid the Istanbul Museum of Archaeology for the excavations there. Sources at the museum who are unfriendly to Pasinli say that the hotel is indeed looking for ways to incorporate the palace remains into a new building, possibly a reconstructed version of a nineteenth-century Ottoman one that stood there.

That the permit was granted is almost more surprising than the discovery of the palace remains. German archaeologists Theodore Wiegand and Ernst Mamboury witnessed the construction of the Ottoman prison, now the hotel, in 1911 and examined the palace sites not requiring excavation, publishing their findings in 1934. French archaeologists surveyed the area during the Allied occupation of the city following World War I, and two years ago Oxford University doctoral student Eugenia Bolognesi also surveyed it.

A Turkish team that has conducted a geophysical investigation of the area since 1990 has located hundreds of anomalies that may indicate buried structures. It initially recommended the closure of the area to traffic and to further building, but was overruled by Pasinli and the commission. Strangely, the geophysical team is now working for Pasinli. The Great Palace of Constantinople "Palatium Magnum" (Turkish: Büyük Saray) was the principal residence of Byzantine emperors from Constantine the Great to Alexios I and the symbolic nerve centre of the empire.

Also known as The Sacred Palace, it was the Byzantine equivalent of the Palatine in Rome. The Great Palace of Constantinople was a large complex of buildings and gardens situated on a terraced, roughly trapezoidal site, measuring 600×500 m, and overlooking the Sea of Marmara to the south-east. The complex was enclosed by the Hippodrome to the west, by the Regia (a ceremonial extension of the Mese), the Augustaion, and the Senate to the north, and by the sea walls to the south and east.

Modern understanding of the Great Palace depends heavily on the literary sources and, to a lesser degree, on the meagre archaeological evidence. Of the few archaeologically explored components of the palace complex, the largest is an apsed hall preceded by a large peristyle court with splendid floor mosaics, which feature hunting and pastoral scenes combined with figures from mythology.

The isolated nature of these finds and the ambiguity of the written sources preclude any comprehensive architectural reconstructions of the palace despite repeated attempts since the 19th century. In its scale and general character the Great Palace must have resembled a city, with numerous buildings, private harbors, avenues, open spaces, terraces, ramps and stairs, gardens, fountains and other amenities, built and rebuilt over nearly eight centuries.

Rebuilding of palace components at new locations, but retaining their old names, along with the changing functions and names of preserved buildings, are among the factors contributing to the confusion in the current state of knowledge about the Constantinople Great Palace. Notwithstanding these problems, it is possible to identify the main stages in its development. The initial phase, under the auspices of Constantine the Great, produced the core of the palace complex, which, by all accounts, must have resembled several other imperial palaces built during the Tetrarchy.

Constantine’s palace was an overtly urban complex, approached by the Regia. Adjacent to the Regia stood the large Baths of Zeuxippos, a public bath also related to the palace compound. The entire western flank of the Great Palace bordered the Hippodrome, while the so-called Kathisma - a component of the palace with the imperial box for viewing the Hippodrome races, and rooms for other ceremonial functions - provided a palpable link between the Great Palace and the city itself.

The second major phase in the development of the Great Palace occurred in the 6th century, during the reigns of Justinian I and Justin II. Justinian’s building programme was spurred in large measure by the damage caused by the Nika riots in 532, and it involved the rebuilding of structures along the north flank of the palace complex, including the Magnaura and the Chalke.

The latter’s ceiling was decorated with mosaics showing Justinian’s victories over the Vandals in North Africa (533-534) and the Goths in Italy and in part of Spain (535-555); in the centre of the ceiling was a portrait of the imperial couple surrounded by senators. Justin II is credited with the construction of the Chrysotriklinos, the octagonal domed throne-room, the resplendent decoration of which was finished by Tiberios I (578-582). The Chrysotriklinos became in effect the new ceremonial nucleus of the palace, modifying the original Constantinian layout.

The Great Palace was expanded again by Justinian II (685-695; 705-711), who built the Lausiakos and the Justinianos, two halls in the vicinity of the Chrysotriklinos. He is also credited with the construction of a wall enclosing the palace, and of another gate, the Skyla, on the south side. This development marks the end of an ‘open’ relationship between the palace and the city, characteristic of Late Antique imperial palaces in general. This change was brought about, in all likelihood, by the growing urban tensions and violence.

During the iconoclastic controversy (726-843) the Chalke acquired a particular significance in the arguments for and against the worship of images. On the building’s façade was an icon of Christ Chalkites (of the Chalke) shown standing on a footstool; in 726 or 730 Leo III Isaurikos (717-741) removed the icon and replaced it with a cross as the first overt act of imperial iconoclasm.

The image of Christ was restored around 787 by Empress Eirene, only to be removed once again by Leo V (813-820) in 813 and replaced by a cross at the start of the second period of iconoclasm. By that time the iconoclastic emperor Theophilos (829-842) had already begun the next major phase in the development of the Great Palace, which continued under Michael II, Basil I and Leo VI.

Theophilos was responsible for the strengthening of the sea walls and for a new two-storey ceremonial complex centred on the Trikonchos, preceded by the Sigma court and surrounded by other pavilions. In its general character, this complex owed as much to the Late Antique palatine tradition as it probably did to the palaces of the Umayyads, with whom Theophilos is known to have maintained close cultural contacts.

Michael III is noted for several building restorations (particularly of the Chrysotriklinos) and adaptations, but his most celebrated addition to the Great Palace was the church of the Virgin of Pharos "Lighthouse", renowned for the relics it contained and for its splendour, if not for its size.

By far the best-known church to be added to the Great Palace was the five-domed Nea Ekklesia under the auspices of Basil I. This emperor was responsible for one of the most extensive building programmes to the Great Palace, which must have substantially altered its appearance. Among his additions were two halls, known as the Kainourgion (the New Hall) and the Pentakoubiklon (a room divided into five bays), and a large court for polo games, known as the Tzykanisterion.

Leo VI is credited with the construction of a sumptuously decorated bathhouse. In the following centuries the amount of construction within the Great Palace of Constantinople diminished. During the reign of Nikephoros II Phokas (963-969) another line of fortification walls was erected, apparently enclosing the shrunken core of the Great Palace.

The final decline of the Great Palace began under Alexios I Komnenos (1081-1118), who moved the imperial residence to the new palace of Blachernai. Despite this shift, the Great Palace retained its ceremonial role for some time to come. Even some new construction occurred, as under Manuel I (1143-1180), who built two halls: the Manouelites and the Mouchroutas. The latter, known to have been the work of a Persian builder, had a painted and gilded stalactite ceiling akin to such ceilings in Islamic architecture.

During the Latin occupation of Constantinople (1204-61) the Great Palace was used, but was also despoiled of its major treasures. The Palaiologan emperors (1261-1453) never attempted to restore the abandoned, slowly decaying complex. Its final demise came in 1489-1490, when a large quantity of gunpowder stored in one of the old buildings exploded, obliterating most of the surviving remnants.

LOCATION SATELLITE MAP

These scripts and photographs are registered under © Copyright 2017, respected writers and photographers from the internet. All Rights Reserved.

No comments:

Post a Comment