Sultanahmet, Fatih - İstanbul - Turkey

GPS : 41°00'14.1"N 28°58'26.2"E / 41.003917, 28.973944

PHOTOGRAPHS ALBUM

PHOTOGRAPHS ALBUM

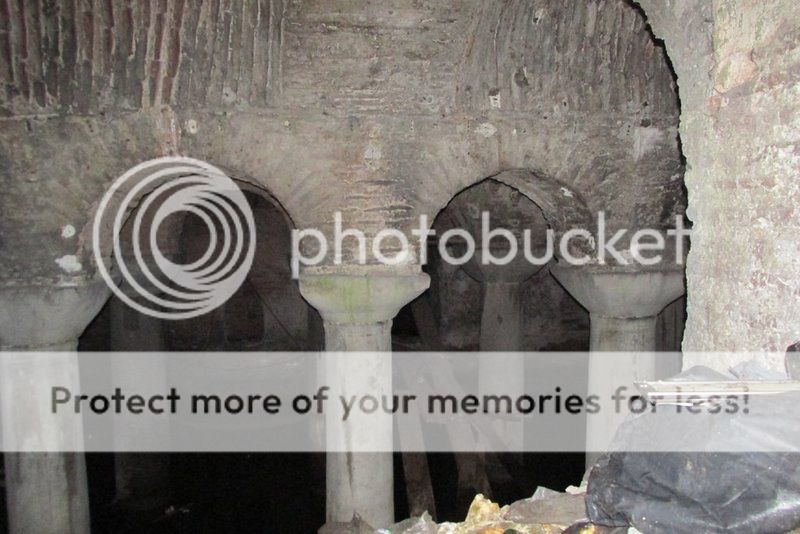

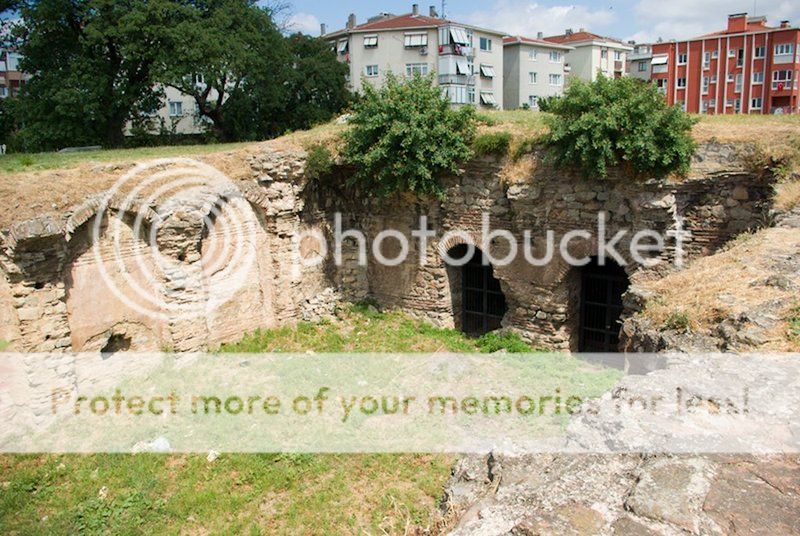

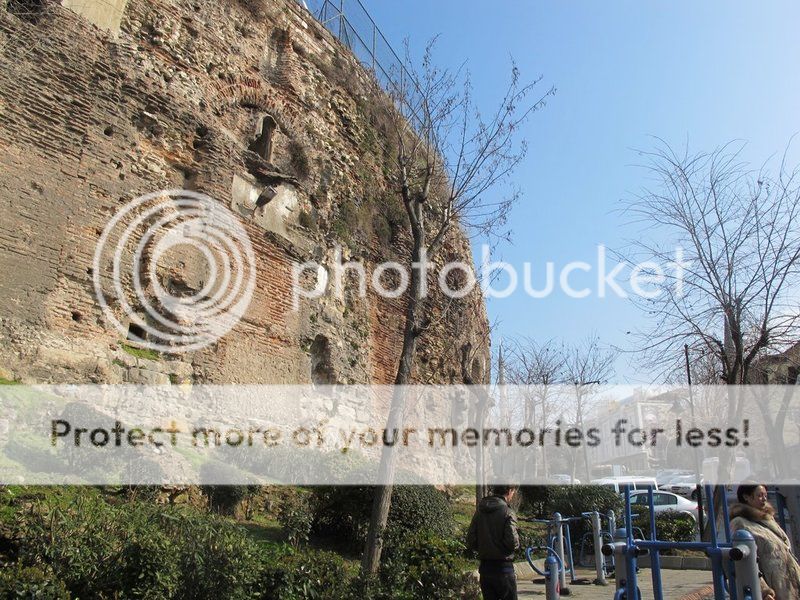

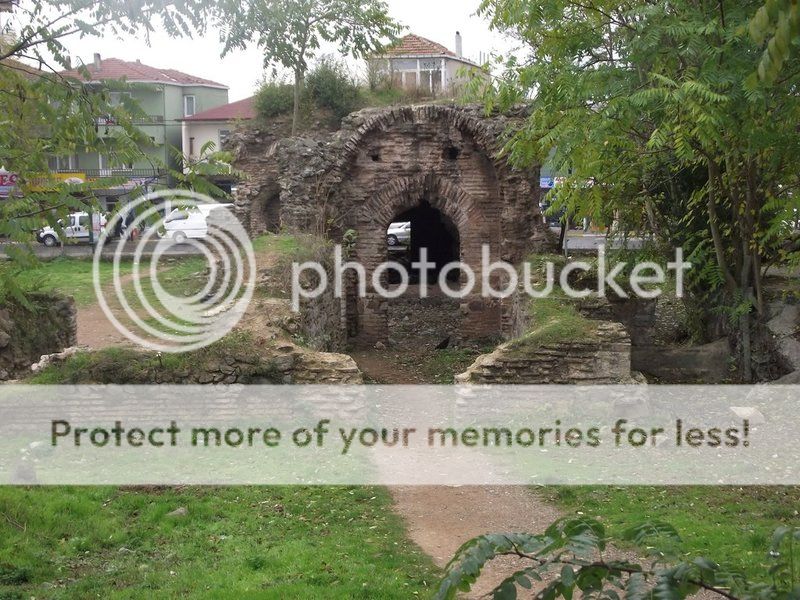

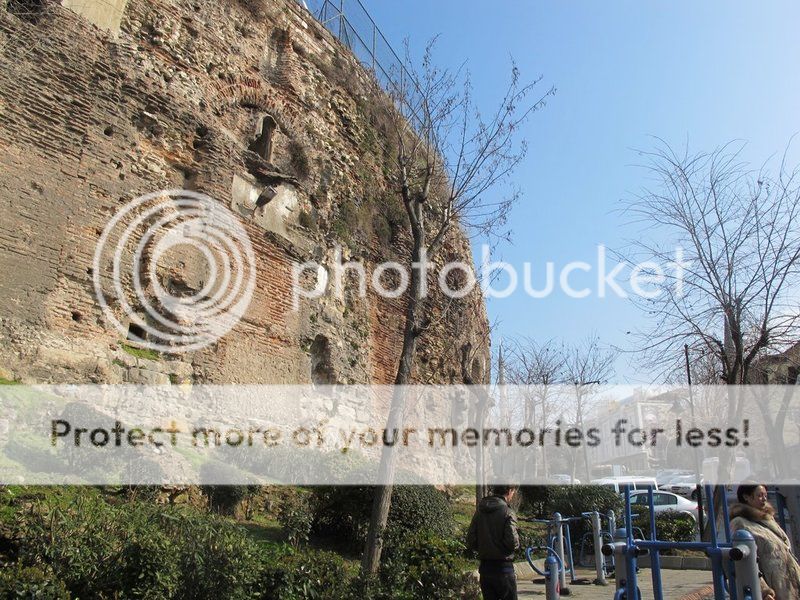

At the southern end of the Hippodrome, where the land begins to slope down to the sea, a series of massive vaults were constructed to serve as a retaining wall for the Sphendone, that curved section of the track where it turns back to the starting gates. In 1927, a British expedition led by Stanley Casson spent four months excavating and studying the Hippodrome, especially the foundation of the Sphendone.

Behind the twenty-five supporting arches (some still visible above) were found a corresponding number of concentric chambers opening out onto a main corridor. After a devastating earthquake in AD 551 (which also collapsed the dome of Hagia Sophia), these arches were bricked up and a series of buttresses added. Sometime later, the chambers themselves were closed off and converted to a cistern.

Around the entire Hippodrome was an arcade of columns, as can be seen in the drawings below. The itinerary of an anonymous Russian pilgrim records that thirty columns still were standing early in the fifteenth century. When Petrus Gyllius (the Latinized version of Pierre Gilles) visited in 1544-1547 as a deputy of François I, seventeen remained, all of them "supported by arched foundations that lie level with the plain of the Hippodrome but rise above the ground to a height of fifty feet". But, he says, they soon were removed by Süleyman (the Magnificent) to build a hospital.

"I was concerned to see them thus demolished, not so much for the use they were intended but because some of them were squared out for paving a bath." The Corinthian capitals of white marble, "made after the most exact plans of ancient architecture," were reshaped to cover a bake house, and the pedestals and entablature to build a wall. A section of column found by Casson in the Hippodrome also is the same size and type as those in the courtyard of the Sultan Ahmet Mosque (right).

Backed against this arcade of columns were tiers of seats, which the crusader Robert de Clari counted as thirty or forty rows. They, too, seem to have been used as paving stones for the courtyard of the mosque. And some, "which had survived until only a few years ago," were taken by Ibrahim Pasha, Süleyman's grand vizier, to construct his palace across from the obelisk of Theodosius.

Originally, the tiers had been built of wood and repeatedly were set ablaze during factional violence in AD 491, 498, and 507 (when an arch also collapsed). The last conflagration occurred during the Nika riot in AD 532, when the factions again set fire to the tiers, burning part of the colonnade. No other fires are reported, and it is presumed that Justinian I rebuilt the seats in marble. Although Gyllius comments on the fine view from the top seats, the Sphendone more often was the scene of public executions and so was especially prized by the populace for the political theater it offered.

Under Valentinian I, for example, the chief eunuch was burned alive at the Sphendone during the chariot races, and a prefect being questioned by the senate was tripped up and fell at the turning post, where he was dragged away by the mob (Chronicon Paschal, 369, 465). Others were mutilated, decapitated, and executed. The last was an attendant to a rival of Andronicus I Comnenus, who had the lamentable young man repeatedly thrust by long poles into a fire made hotter still by brush wood and naphtha.

Andronicus, himself, perished even more miserably in the Hippodrome, being butchered after every indignity while being suspended by his feet near the she-wolf on the spina (349-352). Casson established that the Sphendone was a semicircle, and the diameter of the Hippodrome to be 117.5 meters (385.5 feet) and its length 480 meters (almost 1575 feet). Originally, the track was 4.5 meters (almost 15 feet) below the present surface level, the deposit of earth and debris having accumulated during the construction of the Sultan Ahmet Mosque.

Surprisingly, and in spite of Robert de Clari's remark that "Lengthwise of this space ran a wall, full fifteen feet high and ten feet wide," Casson found no evidence of a spina along the axis and concluded that the monuments, themselves, served the purpose, possibly joined by wooden barriers. Too, the pedestal of the column of Porphyrogenitus was discovered to have been fitted to serve as a fountain, with a spout on each of its four sides. A similar water conduit was found to run beneath the obelisk of Theodosius.

The Serpent Column rests on a reused column capital which, in turn, sits on two water conduits sunk into the original clay bedding of the Hippodrome and also served as a fountain. There even was a tradition that wine, milk, and water poured from the mouths of the serpents. Although Casson suggests that the column originally might have been located elsewhere in the Hippodrome and moved to its present location only at the close of the Byzantine period, it more likely always has been on the spina.

The hippodrome was one of five types of places of public entertainment in cities of Antiquity. The odeon (recital hall) was comparatively small in size and capacity, and was the only one roofed over.

The others, open to the sky, differed in functions: the theater (theatron), semi-circular in shape, intended for various stage presentations; the amphitheater (amphitheatrum or "double theater"), elliptical in shape, developed by the Romans for gladiatorial and animal spectacles; the stadium (stadion), a hair-pin rectangle in shape (with one end curved), intended for foot-racing; and the hippodrome (Roman circus), of essentially the same shape, but larger, for horseback or chariot races. All forms had seating of tiered stone benches built over internal vaulting. Their respective functions could sometimes overlap.

Constantinople's Hippodrome, imitating Rome's archetypal Circus Maximus, was among the largest. In its Byzantine form, it measured somewhere between 450 and 480 meters in length, 117 meters in external width and about 80 meters in internal width. Its estimated seating capacity was 100,000. The southwestern semicircular end (the sphendone, from "sling") was topped by a colonnade. At the straight (northeast) end, there were twelve gates (carceres; kankella, thyrai) that could be opened mechanically at the same moment.

On a tower over these gates stood the famous four bronze horses carried off by the Venetians after 1204 and placed over the portal of the San Marco Basilica. At about the midpoint on the eastern side, above the seats, was the imperial box (kathisma), which connected to the Great Palace complex behind it. Down the center of the arena ran the barrier wall, or spina (euripos), around which the races were run in counterclockwise course.

At each end of the spina was a turning-post or meta (kampter), and along this barrier were mounted various ornaments, as well as frames each holding the pivotable metal figures of seven dolphins, which could be rotated in turn to mark the running of the seven laps in each race. These races, held at regular points each year, were run by charioteers, each in a quadriga, a two-wheeled car pulled by a team of four horses. Between races, acrobats, dancers, and musicians offered entertainment.

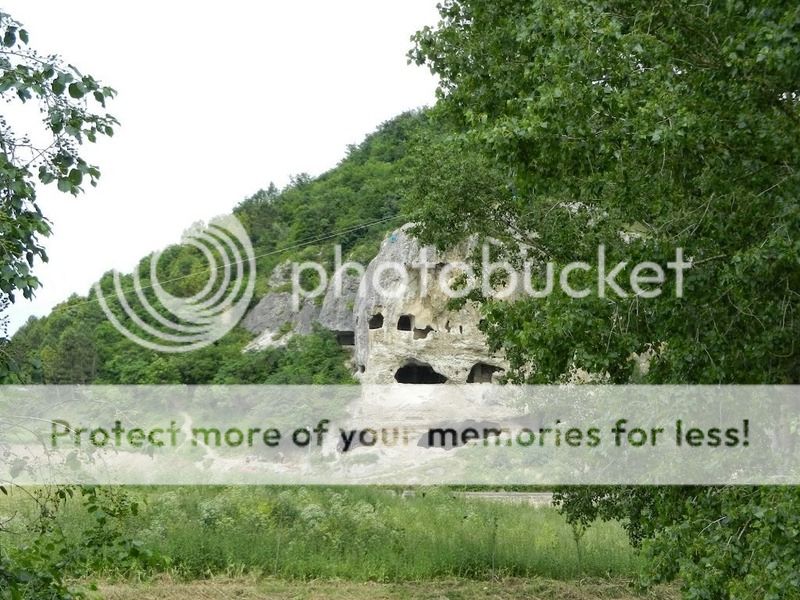

Structurally, the Hippodrome predates Constantinople itself. The ancient Greek city of Byzantium, destroyed by Septimius Severus (193-211) for its disloyalty, was rebuilt by him in 203. His gigantic supporting masonry can still be seen beneath the Hippodrome's sphendone on its sloping south hill. The Severan Hippodrome was left unfinished. It was expanded and completed in the context of the transformation by Constantine the Great (324-337) of old Byzantium into his new capital of Constantinople, finished in 330.

Constantine was followed by his successors in adorning the Hippodrome's spina with sculptural treasures from around the empire, imitating the Circus Maximus.6 There were notable bronze statues, and in the center was placed at some point the great bronze Serpent Column that had been dedicated at Delphi in honor of the Greek victory over the Persians in 479 B.C. The original meanings of these monuments were not always understood fully: the Serpent Column itself was for a while fitted out as a fountain.

To its north, meanwhile, an Egyptian obelisk had been placed. It was originally one of a pair set up near Thebes by Pharaoh Thutmose III in the 5th c. B.C. Its sister was mounted in the Circus Maximus in Rome, while this one was brought to Constantinople. It was shattered in transit, but in 390 the surviving upper third was set up in honor of Emperor Theodosius I (379-395), atop a base carved with triumphal scenes showing the Emperor and his sons, plus scenes of the obelisk's erection.

At the other side of the Serpent Column was constructed, probably also in the fourth century, a built-up masonry obelisk. In the sixteenth century a French traveller gave named it the "Colossus" because of an inscription - comparing it to the ancient Colossus of Rhodes - set on it by Emperor Constantine VII Porphyrogenitos (913-959), to whom this obelisk has also been erroneously attributed.

In the transformation of the city from Byzantium to his new capital, Constantine focused on the adornment of the monumental core of the city, first by finishing the Severan projects. The monumental development that included the emboloi, the Tetrastoon, the Basilica, the Baths of Zeuxippos and the Hippodrome became the cornerstone of the Constantinian plan. The Constantinian manipulations of the extant Severan buildings created a monumental set of interrelated yet independent public spaces that responded to and defined public urban life.

By concentrating five major imperial foundations (the Augustaion, the Basilica, the Hippodrome, the Great Palace and the Baths of Zeuxippos) in a relatively confined area, Constantine sought to give a monumental expression of the romanitas of the urban character of the city: the overarching magnificence of Rome, its empire and its institutions. The Hippodrome and its associated palace was the manifestation of a singularly Roman mentality; it was a combination evident in the Tetrarchic capitals of the Roman world that derived ultimately from the relationship between the Circus Maximus and the imperial residence at Rome.

The image of romanitas conjured by the city’s institutions and monuments was at once general and specific. On the one hand, places as the Hippodrome and the Zeuxippos created a sense of participation in the Roman imperial experience. On the other hand, the specific conjunction of Hippodrome and Palace created a more specifically Roman link that bound Constantinople directly and intimately to the city of Rome, transforming it into the New Rome.

In ancient cities, the theaters were places of lively public assembly as well as entertainment. As proto-Byzantine Constantinople took shape, it developed none of the old open-air theaters, so the Hippodrome became the city's largest place of regular public assembly, as part of an integrated complex. To its northeast lay the great square of the Augustaion, around which stood major public and governmental buildings. Beyond that was the Patriarchate and the Great Church of Hagia Sophia, site of the Empire's spiritual ceremonial.

While the adjacent Great Palace housed court ceremonial, the Hippodrome was the place for political ceremonial. Here, and only here, the Emperor faced the mass of urban populace during regular festivities. Here new Emperors were presented, important executions carried out (e.g., of the general Narses by Emperor Phokas in 603) and celebrations were held (e.g., the triumph the general Belisarius under Justinian in 534).

It was an essential point for triumphal imperial ideology since it enabled the association of racing games with the imperial triumphs; this theme occurs frequently in the imperial iconography and was manifested in the Obelisc of Theodosios I, on the base of which the scene with the emperor presiding the games is juxtaposed with scenes of imperial triumph over the barbarians.

Popular acclamations in the Hippodrome extoled imperial omnipotence as a ritual, in which the main actor was the populace and which remained lively even at a later era, as shown by the Book of Ceremonies. Moreover, the racing operations generated the only institutions allowing some active popular participation. These were the famous demes, the circus factions. Transplanted from Rome to Constantinople (and matched in other cities) were the four fan-clubs, identified by colors, that supported the professional chariot racers, often widely acclaimed celebrities.

The two minor factions, the Whites (Leukoi) and the Reds (Rousioi) were overshadowed and virtually subsumed by the two major ones the Blues (Venetoi) and the Greens (Prasinoi). Each faction (factio; meros, demos) had reserved seats on the western side of the Hippodrome, opposite the kathisma and on either side of the finish-line, plus club-houses and facilities in the vicinity.

As the demes (especially the Greens and the Blues) grew in importance and developed their characteristic features as kinds of political parties, the Hippodrome became a place where the populace ventilated its opinion and staged politically charged acclamations, assuming opposing identities in court partisanship, in social-class ties, and in the highly explosive religious controversies of the day. In order to secure the popular support they needed, emperors often found themselves driven to favour one or other of the demes, whose intervention more than once proved crucial for imperial politics.

Their unruliness reached a peak in January 532 when they temporarily joined forces in the so-called Nika Riots. For nineteen days they defied the Emperor Justinian (527-565), raged destructively through the city, and tried to dethrone him. The disturbances were suppressed only when some 30,000 rioters were caught in the Hippodrome and massacred.

Briefly curtailed, the factional disturbances recurred in the seventh century, but the organizations were reduced to increasingly ceremonial functions by the eighth century, their titular leaders serving tame ritual roles. In fact, the factions' supposed status as substitute "political parties" in their heyday has been exaggerated: their actual members were never more than a fraction of the populace, and, despite a few neighborhood functions, they were little more that rowdy sports clubs.

If the factions were diminished, the popular taste for chariot racing was not reduced, despite long opposition from the Church. As the sport waned and disappeared in the Empire's remaining cities, it persisted as a popular distraction in the capital until final disruption by the Fourth Crusade (1202-04). Visitors in the twelfth century still reported the spectacles offered there. Nevertheless, competition to the old sport came from alternative entertainments, such as Western-style tournaments, particularly favored by the Latin-admiring Emperor Manuel I (1143-1180).

Grimmer function was served when the urban mob presided over the savage torture and execution of deposed Emperor Andronikos I (1183-1185). Already decrepit structurally, the Hippodrome began to fall into decay during the Latin occupation (1204-61), its treasures and decorations looted or destroyed by the Crusaders. In Byzantium's two final centuries the Hippodrome became a ruin, though still used occasionally for equestrian jousts.

When the Ottoman Turks took the city in 1453, they left the site open, using it as an exercise area called the Atmeydanı (the Field of Horses). But the sphendone colonnade was pulled down in 1550, while the old seating structures were gradually encroached upon and cannibalized by new Turkish buildings (e.g., Ibrahim Pasha's Palace in the sixteenth century, Sultan Ahmet I's "Blue Mosque" in the seventeenth).

In 1700 some rowdy members of a Polish diplomatic delegation decapitated the Serpent Column, carrying off its top; though the upper head of one of the three serpents has survived in the Archaeological Museum of Istambul. In 1890 the French designer Bouvard began re-designing a reduced park within the old Hippodrome space.

This design was completed after a decade at the northeast corner with the elaborate fountain donated to Sultan Abdülhamit II by Kaiser Wilhelm II in honor of his visit to the city in 1895. Some scattered excavations around the area have revealed small traces of the Hippodrome and its surroundings. But this park, an undeniably lovely public place, still incorporates at its center the two obelisks and the trunk of the Serpent Column.

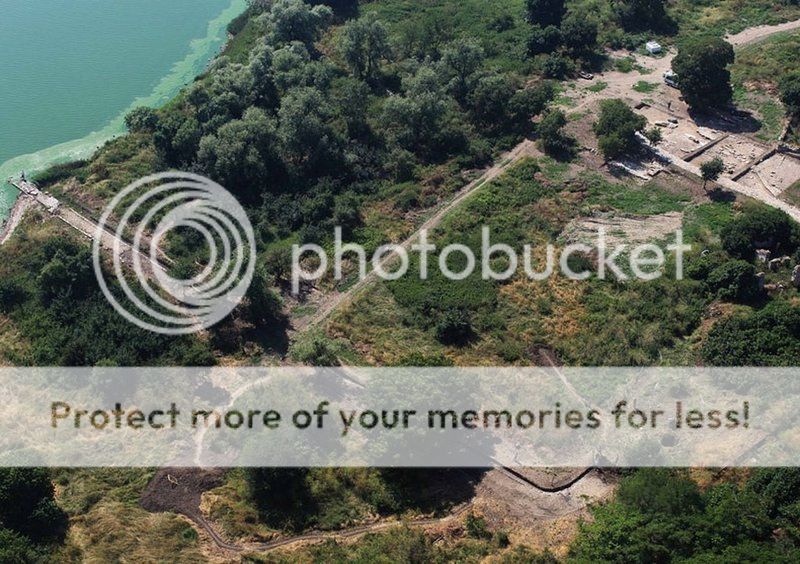

LOCATION SATELLITE MAP

These scripts and photographs are registered under © Copyright 2017, respected writers and photographers from the internet. All Rights Reserved.