GPS : 41°01'54.4"N 28°58'30.1"E / 41.031788, 28.975019

PHOTOGRAPHS ALBUM

Inaugurated on 8 June 2005, Pera Museum is a private museum founded by Suna and İnan Kıraç Foundation with the aim of offering a broad range of high-quality culture and arts services.

The Museum is located in the historic building of the former Hotel Bristol in Tepebaşı, renovated between 2003 and 2005 by restorer architect Sinan Genim, who preserved the façade of the building and transformed the interior into a modern and fully equipped museum.

Pera Museum shares its three permanent collections “Orientalist Paintings”, “Anatolian Weights and Measures”, and “Kütahya Tiles and Ceramics,” as well as the values that these collections represent, with the public through exhibitions, publications, audio-visual events, educational activities, and academic works, striving to transmit these values to future generations.

Having organized joint projects with leading international museums, collections, and foundations including Tate Britain, Victoria and Albert Museum, St. Petersburg Russian State Museum, JP Morgan Chase Collection, New York School of Visual Arts, and the Maeght Foundation, Pera Museum has introduced Turkish audiences to countless internationally acclaimed artists, among them Jean Dubuffet, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Rembrandt, Niko Pirosmani, Josef Koudelka, Joan Miró, Akira Kurosawa, Marc Chagall, Pablo Picasso, Fernando Botero, Frida Kahlo, Diego Rivera, and Goya.

Since its inauguration, Pera Museum collaborates annually with national and international institutions of art and education to hold exhibitions that support young artists. All of the Museum’s exhibitions are accompanied by books, catalogues, audio-visual events, and education programs. Standing out with its seasonal programs and events, Pera Film offers visitors and film buffs a wide range of screenings that extend from classics and independent movies to animated films and documentaries, as well as special shows paralleling the temporary exhibitions’ themes. Pera Museum has evolved to become a leading and distinguished cultural center in one of the liveliest quarters of İstanbul.

PORTRAITS FROM THE EMPIRE

Throughout the ages, the Orient has attracted the interest of the West. European intellectual and artists have been mesmerized since the earliest times by this presumably mysterious and relatively closed world. As a natural consequence, during various periods many artists, either by traveling themselves or by traveling in their imaginations, sought to discover the essence of the Orient, and depicted or expressed in their works either the real Orient or their own visions of it.

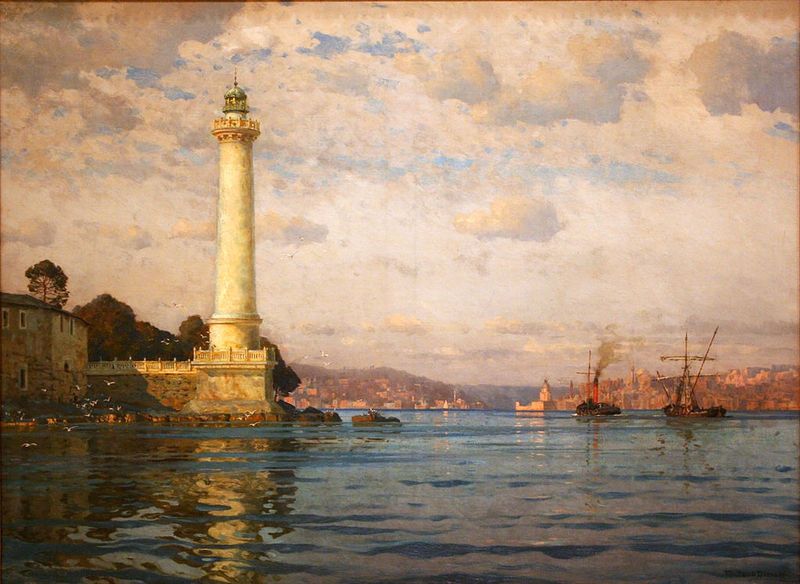

The movement known as Orientalism in European art, which appeared in conjunction with the Romanticist movement of the 19th century, focused on the East, primarily in the lands of the Ottoman Empire. Even long before the rise of Orientalism in European art, many European artists, fascinated by their first glimpses of the mysterious East and by the Turquerie fashion which was the result of the new relations with the Ottoman world. For nearly two hundred years, starting from the 18th century, numbers of painters, some of whom became known as the Bosphorus Painters, worked intensively in the lands of the Empire and depicted the Ottoman world its various aspects, consequently engraving those images in mankind's visual memory.

The exhibition Portraits from the Empire sheds light on a special part of this opulent world. Almost sixty paintings selected from the Suna and İnan Kıraç and Sevgi and Erdoğan Gönül collections bring us face to face with the peoples of the Ottoman world, their portraits and portrayals, sometimes very familiar and sometimes remote, even nearly foreign, in their physiognomies. These paintings, most of them created before the eye of the camera replaced the human eye, in the times when observing, studying, interpreting and depicting the world was the priority of painters, present the lost faces of an era long past with amazing reality and vividness.

Sultans and Portraits

The Ottomans played a prominent role in the power balance of Europe from the 15th century, as their territories in the Mediterranean region and Europe expanded, and this led to increasing European interest in Turkey and the Turks, an interest focused above all on the structure of the Ottoman state. In the 18th century in particular, growing political and trade relations brought not only many diplomats, merchants and travelers to the Ottoman capital, but also many artists, most of whom were employed in diplomatic circles. Under their influence Western style portraiture began to gain ground in Ottoman court circles.

There had been a tradition of painting portraits of the Ottoman sultans in the miniature technique since the 16th century, usually in the form of portrait albums depicting all the Ottoman sultans from Sultan Osman, founder of the dynasty, onwards. From the 18th century this portrait series began to be executed using different techniques, such as oil painting, while at the same time local studios specializing in the production of portrait albums were established in Istanbul. From the reign of Selim III many local artists made portraits using western techniques, and Selim's nephew Mahmud II had his own portraits painted in oil, depicting him in the new western style dress that he had introduced, and had these hung in government offices.

Portraying Ottoman Society

European artists who came to Istanbul as members of diplomatic entourages depicted scenes from different parts of the Ottoman capital, distinctive costumes worn by the different classes of people in the empire, and portraits of foreign ambassadors, interpreters, and increasingly of Ottoman dignitaries. Vanmour, for example, in addition to several audience scenes and pictures of Istanbul, painted various state officials in their typical costume, and these were published in Marquis de Ferriol's Recueil de cent estampes representant differentes nations du Levant in 1714. A number of paintings of similar size in various collections and museums are thought to belong to this series of oil paintings by Vanmour.

One of the most notable of the European artists who worked in Istanbul in the 18th century was a knight of Malta Antoine de Favray, who arrived in Istanbul in 1762 and was employed by the French ambassadors Comte de Vergennes and Comte de St. Priest until 1771. His portraits of Vergennes and his wife show the couple not only dressed in Turkish costume but even seated in oriental style.

This tradition of painting, particularly portraiture, introduced by western artists, gradually spread from court and diplomatic circles to broader sectors of society; first to high-ranking state officials and then to leading Ottoman families, whose members increasingly commissioned portraits of themselves. Even more importantly, this tradition of oil painting influence local artists, one of the most renowned being Osman Hamdi Bey, who despite his oriental birth, did many works that place him among the artists of the orientalist movement.

The world of women and the "harem" as seen by western painters

In Orientalist iconography women and pictures of women hold an important place. To a large extent this is related to the fantasy of the 'harem,' which is one of the most important elements shaping both Orientalist literature and Orientalist painting. In Muslim countries the Arabic word 'harem', meaning a sacred place forbidden to enter, refers to the part of palaces and houses belonging to the women of the family. This concept of privacy and the sense of mystery it generated, particularly with respect to the palace, made the harem the most fascinating aspect of eastern life in the eyes of westerners.

Although Orientalist painters based their pictures of the harem mainly on written sources, they sometimes also used non-Muslim models or called on their powers of imagination. The imagined eroticism of life behind those closed doors, as much as the idea of its inaccessibility to the outside world, was what spurred interest in the harem. European men envisaged eastern women as sultanas or concubines living in a timeless world with nothing to do but prepare themselves for their masters.

In contrast, accounts and pictures by European women invited to visit Ottoman harems presents a different world. Their harems, although with occasional traces of A Thousand and One Nights, mainly portray dignified and respectable home environments. But it was writings and portrayals by men that dominated the Orientalist discourse, since they responded to the expectations of their western audience, unlike the more realistic ones by women.

Ottoman women and daily life

For the harems women, whose daily recreational pursuits were largely confined to conversation, embroidery, drinking coffee and smoking pipes, receiving guests and holding musical gatherings were occasions that added colour to their lives. In the palace harem there were orchestras and groups of dancers consisting of female slaves, and the female musicians were taught by the most eminent teachers of the time. Singing and playing music was one of the most popular pursuits of women at the palace and the upper echelons of society.

Ottoman women had limited opportunities for activities outside the home. The upper-class women rarely went shopping, most of their needs being met by servants or peddler women. Wedding celebrations and feasts, visits to holy tombs and sufi lodges, and friends and relatives, social gatherings known as 'helva nights', Mevlit ceremonies, weekly visits to the public baths, and above all picnics and country excursions in spring and summer were events that took women out of their homes. Western men, who had to make do with second-hand accounts of Ottoman harem life, only had the opportunity to see these women for themselves when they were traveling from place to place, shopping in the company of eunuchs, or enjoying country outings.

The most popular excursion places were Kağıthane on the Golden Horn and Göksu and Küçüksu on the Asian shore of the Bosphorus. Pleasing scenes of women in gauzy yashmaks and colourful outer robes promenading in their carriages, strolling in meadows, or being rowed along in graceful caiques, lacy sunshades in hand, were a favourite topic for western painters.

Women, costumes, portraits

Portraits focusing on women's costume form an important category of these pictures by western artists. Although the artists did not have the opportunity to observe Ottoman women at home, they could see women's clothing for themselves, and many of them purchased Ottoman garments to take back home with them and used these as studio accessories. Consequently we find many 18th and 19th century paintings of real European women or imaginary women dressed in Ottoman costume. Among diplomatic circles in Istanbul it was fashionable to be portrayed in Ottoman costume.

Painters unable to depict Ottoman women in indoor attire from life, instead portrayed Greek, Armenian, Jewish and Levantine women in such scenes. In fact, however, Ottoman palace women and those of the upper classes were keen to have their portraits painted, and western women painters such as Henriette Brown and Mary Walker were in popular demand. However, when these portraits showing them dressed in European clothing of the latest fashion were completed, they were not hung in full view, but concealed in cupboards or by a curtain so that the male servants of the household should not see them.

AMBASSADORS AND PAINTERS

Since its earlier periods, The Ottoman Empire, has established intense relations with European states. Urged by curiosity and a certain degree of fear at times, the West's efforts, on the other hand, to be acquainted with and understand this government of immense military power and source of political authority, emerged as a political exigency. Undoubtedly, the encounter of markedly different cultures bore the most enduring fruit in the realm of arts.

Wars, the increase of trade as a means for mutual prosperity, and conflicts of status were the most significant factors behind the intense traffic of diplomacy. Sprawled across a vast geography, the Ottoman Empire welcomed more ambassadors than it sent to other countries, particularly until the 19th century; these ambassadors were embraced, per Ottoman tradition.

In turn, western ambassadors were prompted by the need to document the cities, particularly İstanbul, social structure, customs, administrative and military organization of the Ottoman Empire; apart from the reports they drafted upon their return, they also took advantage of the gifts and paintings they carried along. Often presumed to be true-to-life visual documents, such paintings thus became the most evident expressions of respectability and social status, and attained a special place and meaning, partly due to their potential to address the masses.

The works that ambassadors commissioned to artists they added to their retinue en route to the East or to their local counterparts they encountered during service, evolved into books with engravings or collections decorating the walls of European chateaus, and served as source material for works by other artists, thus generating a large visual repertoire on the Ottoman world. Ottoman ambassadors sent to European countries were subjects of monumental portraits painted by leading European artists of the period, immortalizing these historic visits.

This selection from the Suna and İnan Kıraç Foundation Orientalist Painting Collection not only allows us to travel across the meandering paths of diplomatic history under the guidance of art, but it also introduces us to intriguing personalities. Ambassadors and painters continue to communicate with us through a silent yet equally rich and colorful language of expression, present their reports and letters, and share with us their respective periods, worldviews, travels and experiences, as well as the ceremonies they joined. Listening to their extraordinary tales, it is impossible not to be enraptured by the splendor and elegance of a lost age.

Ambassador's Portrait

Often used as one of the clearest indications of status and identity in western art since Antiquity, portraits also served a similar purpose for ambassadors. Furthermore, documenting the physiognomy of ambassadors through portraiture was also regarded as a precautionary measure against espionage. Portraits were painted of European ambassadors sent to the Ottoman Empire as high-level officials that have attained great respectability; artists to which these portraits were commissioned strived to reflect not only the physiognomy of the ambassadors, but the power and authority of the state and the ruler they represented.

The Ottoman State's political, military, commercial, and cultural relations with European states gained momentum from the 18th century onwards. In turn, the visits Ottoman ambassadors paid to western countries accelerated the spread of the Turquerie fashion of the period. While portraits of Ottoman ambassadors painted by renowned artists of the countries to which they were assigned served to honor the Ottoman Sultan and his representative, they also nurtured the West's penchant for exoticism.

There is no doubt that the ever-changing trends, fashions, as well as the purpose of diplomatic visits and political relations were reflected in the portraits. For example, while Kozbekçi Mustafa Ağa, who was sent to Sweden to collect debts, is portrayed standing -like a western emperor-, Yusuf Agâh Efendi, who left for England in the late 18th century as the first permanent ambassador of the Ottoman Porte, is depicted entirely in an eastern pose with the rosary beads he holds in his hand against a western background. When French Ambassador Comte de Vergennes commissioned portraits of himself and his wife in Ottoman attire per the Turquerie fashion, he was depicted in an eastern pose, thereby clearly emphasizing that he served as ambassador in İstanbul.

Paintings depicting the audience of European ambassadors at the Ottoman Palace constitute a special group of works that not only demonstrate a diplomatic event and reflect court traditions and officials in a range of attires, but they also act as portraits of foremost individuals, such as the sultan and the grand vizier. Borne directly out of and as a consequence of the realm of ambassadorial service, the best-known examples of this genre have been executed by Jean-Baptiste Vanmour.

Ambassador's Artist

Paintings by artists under the patronage of western ambassadors mainly carried weight as visual documents at times, whereas in other instances, they were appreciated as works that commemorated this prestigious service, popularizing and transmitting the name of each ambassador from one country or generation to the next. It is possible to assume that the Ottoman scenes Hans Ludwig von Kuefstein -the Holy Roman Empire's ambassador to the Ottoman Porte- commissioned were documentation-oriented works when they were initially executed.

On the other hand, Recueil Ferriol, the book of engravings that Marquis Charles de Ferriol had published based on the paintings of Jean-Baptiste Vanmour had a considerable impact; not only did the book immortalize the ambassador's legacy, but it influenced other artists with the subsequent editions released in different countries at different times.

As of the 18th century, western artists living in İstanbul became an indispensible part of the European way of social life developed around the embassies in Pera. Conceived as a "suburb of Paris," this western setting provided painters with a milieu from which they received commissions that enabled them to meet their social needs and thus sustained their life in İstanbul.

The interest ambassadors such as Choiseul-Gouffier and Robert Ainslie had in the archaeology and picturesque views of Antiquity during the second half of that century, as well as the paintings they commissioned and books they published in line with their world view reflecting the ideology of the Enlightenment, appear to be competing with one another as the harbingers of 19th-century Romanticism.

By the 19th century, western ambassadors assumed the role of patrons for Orientalist painters in İstanbul, such as Fabius Brest or Fausto Zonaro, who ventured out towards the exotic East independently of a diplomatic entourage. Similar, for example, to his painting that depicts British ambassador Sir Philip W. Currie's daughter in a palanquin to be used on her wedding ceremony, Zonaro received commissions from ambassadors and ambassadorial circles prior to becoming Abdülhamid II's court painter, and he was introduced to the Ottoman Palace by way of Russian ambassador Aleksandr Nelidov.

OSMAN HAMDİ BEY

An Ottoman intellectual raised by the Tanzimat Era… An exceptional personality, who made substantial, diversified and lifelong contributions to various fields of culture and arts, such as painting, archaeology, museology, and art education.

More than 100 years after his death, the legacy Osman Hamdi Bey left behind lives in the works of academics, institutions, and museums. He continues to make headlines, draw attention, be heard, and become the topic of heated debates. This special section dedicated to Osman Hamdi Bey at the Sevgi and Erdoğan Gönül Gallery of Pera Museum not only displays different aspects of his impassioned relationship with the art of painting through his works included in the Suna and İnan Kıraç Foundation Collection, but it also pays tribute to his multifaceted personality.

LOCATION SATELLITE MAP

WEB SITE : Pera Museum

MORE INFO & CONTACT

E-Mail : info@peramuzesi.org.tr

Phone : +90 212 334 9900

Fax : +90 212 245 9512

These scripts and photographs are registered under © Copyright 2017, respected writers and photographers from the internet. All Rights Reserved.

No comments:

Post a Comment