GPS : 41°00'48.0"N 28°57'37.0"E / 41.013333, 28.960278

PHOTOGRAPHS ALBUM

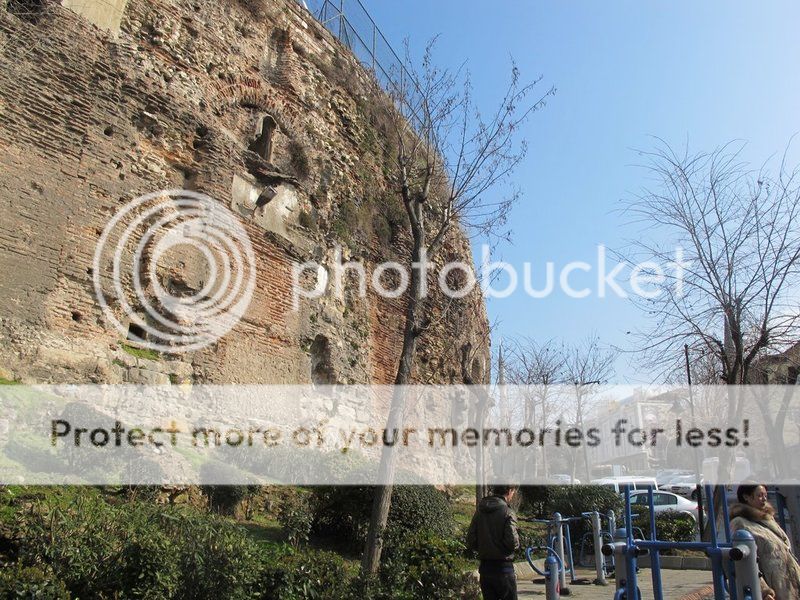

The mosque is located in the Fatih district of Istanbul, Turkey, in the picturesque neighborhood of Vefa, and lies immediately to the south of the easternmost extant section of the aqueduct of Valens, and less than one km to the southeast of the Vefa Kilise Mosque. Located next to the Bozdoğan aqueduct at Vezneciler in Eminönü, the mosque was originally a church. Dating from the late Roman period, it was modified several times and used for different purposes. Used initially as a lavish palace bath, it then became a rich Kommen church, a mosque, a shanty house and finally a mosque again.

Kalenderhane Mosque (Turkish: Kalenderhane Camii) is a former Eastern Orthodox church in Istanbul, converted into a mosque by the Ottomans. With high probability the church was originally dedicated to the Theotokos Kyriotissa. This building represents one among the few extant examples of a Byzantine church with domed Greek cross plan.

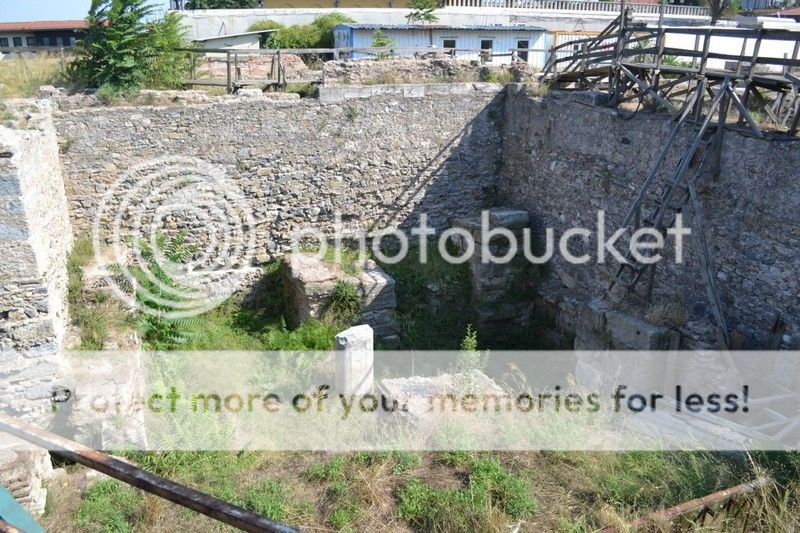

The first building on this site was a Roman bath, followed by a sixth-century (the dating was based on precise coin finds in stratigraphic excavation) hall church with an apse laying up against the Aqueduct of Valens. Later - possibly in the seventh century - a much larger church was built to the south of the first church. A third church, which reused the sanctuary and the apse (later destroyed by the Ottomans) of the second one, can be dated to the end of the twelfth century, during the late Comnenian period.

It may date to between 1197 and 1204, since Constantine Stilbes alluded to its destruction in a fire in 1197. The church was surrounded by monastery buildings, which disappeared totally during the Ottoman period. After the Latin conquest of Constantinople, the building was used by the Crusaders as a Roman Catholic church, and partly officiated by Franciscan clergy.

After the conquest of Constantinople in 1453, the church was assigned by Sultan Mehmed II personally to the Kalenderi sect of the Derwishes. The Dervishes used it as a zaviye and imaret (public kitchen), and the building has been known ever since as Kalenderhane (Turkish: "The house of the Kalenderi"). Some years later, Arpa Emini Mustafa Efendi built a Mektep (school) and a Medrese.

Originally, during the Latin occupation of the 12th century, the mosque was a Catholic Italian church. It was later used as a religious establishment by the Kalenderi sect after the conquest of Istanbul by Sultan Mehmet, the Conqueror. Babüssaade Ağası Maktul Beşir Ağa converted it into a mosque in the first half of the 18th century. A fire caused extensive damage in the 19th century, and it was renovated in 1854. Lightning struck the minaret in 1930, it was then abandoned.

It was later researched and excavated by Harvard University and İstanbul Technical University between 1966-1975. It was restored in 1968 and re-opened for worship. The walls are a mixture of stone and brick. A large dome spans the ceiling. The inner walls are covered by colored marble and engraved ornamentation.

Before it was converted into a mosque by Maktul Beşir Ağa (the chief officer of the Ottoman Palace), it was originally used as monastery and later as church. In chronological order, it was first converted from the Palace Bath House into the Comnenian church, and was later used as a zawiya (zaviye) after the conquest, after which it was converted into a little mosque.

Monastery rooms were converted into a dervish lodge, and the main place of worship place was converted into the semahane. Therefore, it is considered as the oldest semahane. In 1747, Kızlarağası Beşir Ağa built a altar (mihrab), pulpit (minbar) and mahfil, completing the conversion of the building into a mosque. The mosque’s minaret, restored in 1854, collapsed due to a lightning strike in 1930.

In 1746, Hacı Beşir Ağa (d. 1747), the Kızlar Ağası of the Topkapı Palace, built a mihrab, minbar and mahfil, completing the conversion of the building into a mosque. Ravaged by fire and damaged by earthquakes, the mosque was restored in 1855 and again between 1880 and 1890. It was abandoned in the 1930s, after the collapse of the minaret due to lightning, and the demolition of the Medrese.

The conservation of the building dates from the 1970s, when it was extensively restored and studied in a ten-year effort by Cecil L. Striker and Doğan Kuban, who restored its twelfth century condition. Moreover, the minaret and the mihrab were rebuilt, which allowed the mosque to reopen for worship.

The restoration also provided a solution to the problem of the dedication of the church: while before it was thought that the church was named after Theotokos tēs Diakonissēs (Virgin of the Deaconesses) or Christos ho Akataleptos (Christ the Inconceivable), the discovery of a donor fresco in the southeastern chapel and of another fresco over the main entrance to the narthex both bearing the word "Kyriotissa" (Greek for Enthroned), makes highly probable that the church was dedicated to the Theotokos Kyriotissa.

The building has a central Greek Cross plan with deep barrel vaults over the arms, and is surmounted by a dome with 16 ribs. The structure has a typically middle Byzantine brickwork with alternating layers of brick and stone masonry. The entry is via an esonarthex and an exonarthex (added much later) in the west side. An upper gallery over the esonarthex, following the same plan of the one existing in the Church of the Pantokrator, was removed in 1854. Also the north and south aisles along the nave were destroyed, possibly during the nineteenth century too.

The tall triple arches connecting the aisles with the nave are now the lower windows of the church. The sanctuary is on the east side; however, the reconstructed mihrab and minbar are in a corner to obtain the proper alignment with Mecca. Two small chapels named prothesis and diakonikon, typical of the Byzantine churches of the middle and late period have survived. The interior decoration of the church, consisting of beautiful colored marble panels and moldings, and of elaborated icon frames, is largely extant.

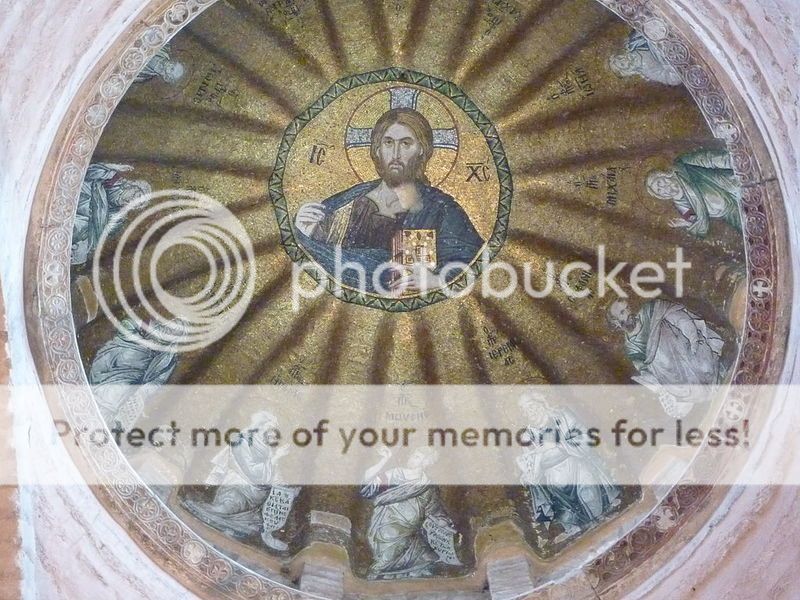

The building possesses two features which both represent an unicum in Istanbul: a mosaic, one meter square, representing the "Presentation of Christ", which is the only pre-iconoclastic exemplar of a religious subject surviving in the city, and a cycle of frescoes of the thirteenth century (found in a chapel at the southeast corner of the building, and painted during the Latin domination) portraying the life of Saint Francis of Assisi.

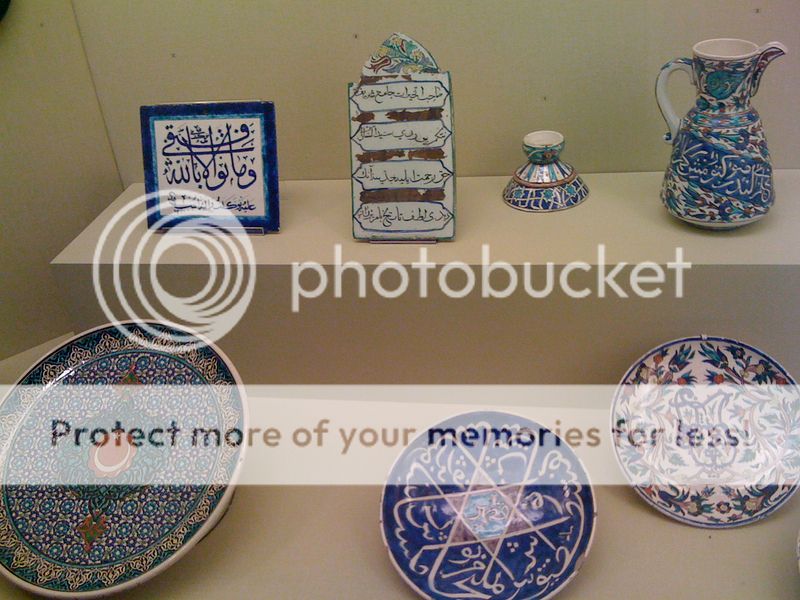

This is the oldest known representation of the saint, and may have been painted only a few years after his death in 1226. The frescoes of St. Francesco and the mosaic panel depicting "the Presentation of Christ", which were discovered in the archaeological expedition preceding the restoration, have been partially restored and are displayed in the Archaeological Museum of Istanbul. Other findings from the 1966 expedition are displayed in a small museum located in the diaconicon of the Kalenderhane Mosque.

The church has a Greek cross or cross-domed plan, preceded by an inner and outer narthex to the west, and with sanctuary to the east. The side entrances from the inner narthex were closed in the period following the Latin invasion. There was also an upper gallery to the inner narthex, which was possibly removed during the 1854 reconstruction, and windows were opened on the northern façade inside the grand arch that was previously obscured by the gallery.

The aisles flanking the nave to the north and south are also thought to have been removed at this time and neither was rebuilt during the 1966 restoration; the triple arches that used to link the nave to the aisles now form the lower tier of windows on the north and south façades. The sanctuary, which was probably replaced by a straight wall with a mihrab during the 18th century conversion, was rebuilt during the restoration and the restored mihrab was moved into the sanctuary apse. The foundations of the sanctuary, which guided the reconstruction, contained the footprint of a smaller mihrab built earlier for the zawiya.

The chapels of prothesis and the diaconicon, located to the north and south of the sanctuary, are complex in plan and incorporate fragments of chapels and apses from earlier structures. Two elaborate icon frames, located on the piers flanking the sanctuary, provide information about the non-extant iconostasis, which rose to the level of the vaults. The original decoration of the church has been largely maintained and consists of polychrome marble revetments and moldings.

It has come into the center of the Kalenderhane Mosque from the narthex covered with vaults. The center of the primary structure is covered by a pendant dome. The central dome of the mosque is supported by a barrel vault, so the ceiling structure is visible. The walls of the mosque consist of both bricks and stones. The inner walls are decorated with beautiful colored marble panels and reliefs. It is now open for worship and to domestic and foreign visitors.

The church has a Greek cross or cross-domed plan, preceded by an inner and outer narthex to the west, and with sanctuary to the east. The side entrances from the inner narthex were closed in the period following the Latin invasion. There was also an upper gallery to the inner narthex, which was possibly removed during the 1854 reconstruction, and windows were opened on the northern façade inside the grand arch that was previously obscured by the gallery.

The aisles flanking the nave to the north and south are also thought to have been removed at this time and neither was rebuilt during the 1966 restoration; the triple arches that used to link the nave to the aisles now form the lower tier of windows on the north and south façades. The sanctuary, which was probably replaced by a straight wall with a mihrab during the 18th century conversion, was rebuilt during the restoration and the restored mihrab was moved into the sanctuary apse.

The foundations of the sanctuary, which guided the reconstruction, contained the footprint of a smaller mihrab built earlier for the zawiya. The chapels of prothesis and the diaconicon, located to the north and south of the sanctuary, are complex in plan and incorporate fragments of chapels and apses from earlier structures. Two elaborate icon frames, located on the piers flanking the sanctuary, provide information about the non-extant iconostasis, which rose to the level of the vaults. The original decoration of the church has been largely maintained and consists of polychrome marble revetments and moldings.

The church belongs to the domed-cross type. The central area is cruciform, with barrel vaults over the arms and a dome on the centre. As the arms are not filled in with galleries this cruciform plan is very marked internally. Four small chambers, in two stories, in the arm angles bring the building to the square form externally.

The upper stories are inaccessible except by ladders, but the supposition that they ever formed, like the similar stories in the dome piers of S. Sophia, portions of continuous galleries along the northern, western, and southern walls of the church is precluded by the character of the revetment on the walls. In the development of the domed-cross type, the church stands logically intermediate between the varieties of that type found respectively in the church of S. Theodosia and in that of SS. Peter and Mark.

The lower story of the north-western pier is covered with a flat circular roof resting on four pendentives, while the upper story is open to the timbers, and rises higher than the roof of the church, as though it were the base of some kind of tower. It presents no indications of pendentives or of a start in vaulting. The original eastern wall of the church has been almost totally torn down and replaced by a straight wall of Turkish construction.

Traces of three apses at that end of the building can, however, still be discerned; for the points at which the curve of the central apse started are visible on either side of the Turkish wall, and the northern apse shows on the exterior. The northern and southern walls are lighted by large triple windows, divided by shafts and descending to a marble parapet near the floor. The dome, which is large in proportion to the church, is a polygon of sixteen sides. It rests directly on pendentives, but has a comparatively high external drum above the roof. It is pierced by sixteen windows which follow the curve of the dome.

The flat, straight external cornice above them is Turkish, and there is good reason to suspect that the dome, taken as a whole, is Turkish work, for it strongly resembles the Turkish domes found in S. Theodosia, SS. Peter and Mark, and S. Andrew in Krisei. The vaults, moreover, below the dome are very much distorted; and the pointed eastern arch like the eastern wall appears to be Turkish. When portions of the building so closely connected with the dome have undergone Turkish repairs, it is not strange that the dome itself should also have received similar treatment.

In the western faces of the piers that carry the eastern arch large marble frames of considerable beauty are inserted. The sills are carved and rest on two short columns; two slender pilasters of verd antique form the sides; and above them is a flat cornice enriched with overhanging leaves of acanthus and a small bust in the centre. Within the frames is a large marble slab. Dr. Freshfield thinks these frames formed part of the eikonostasis, but on that view the bema would have been unusually large.

The more probable position of the eikonostasis was across the arch nearer the apse. In that case the frames just described formed part of the general decoration of the building, although, at the same time, they may have enclosed isolated eikons. Eikons in a similar position are found in S. Saviour in the Chora. The marble casing of the church is remarkably fine.

Worthy of special notice is the careful manner in which the colours and veinings of the marble slabs are made to correspond and match. The zigzag inlaid pattern around the arches also deserves particular attention. High up in the western wall, and reached by the wooden stairs leading to a Turkish wooden gallery on that side of the church, are two marble slabs with a door carved in bas-relief upon them. They may be symbols of Christ as the door of His fold.

The church has a double narthex. As the ground outside the building has been raised enormously (it rises 15-20 feet above the floor at the east end) the actual entrance to the outer narthex is through a cutting in its vault or through a window, and the floor is reached by a steep flight of stone steps. The narthex is a long narrow vestibule, covered with barrel vaults, and has a Turkish wooden ceiling at the southern end.

The esonarthex is covered with a barrel vault between two cross vaults. The entrance into the church stands between two Corinthian columns, but they belong to different periods, and do not correspond to any structure in the building. In fact, both narthexes have been much altered in their day, presenting many irregularities and containing useless pilasters.

Professor Goodyear refers to this church in support of the theory that in Byzantine buildings there is an intentional widening of the structure from the ground upwards. 'It will also be observed,' he says, 'that the cornice is horizontal, whereas the marble casing above and below the cornice is cut and fitted in oblique lines.... The outward bend on the right side of the choir is 111⁄2 inches in 33 feet. The masonry surfaces step back above the middle string-course. That these bends are not due to thrust is abundantly apparent from the fact that they are continuous and uniform in inclination up to the solid rear wall of the choir.'

But in regard to the existence of an intentional widening upwards in this building, it should be observed : First, that as the eastern wall of the church, 'the rear wall of the choir,' is Turkish, nothing can be legitimately inferred from the features of that wall about the character of Byzantine construction. Secondly, the set back above the middle string-course on the other walls of the church is an ordinary arrangement in a Byzantine church, and if this were all 'the widening' for which Professor Goodyear contended there would be no room for difference of opinion.

The ledge formed by that set back may have served to support scaffolding. In the next place, due weight must be given to the distortion which would inevitably occur in Byzantine buildings. They were fabrics of mortar with brick rather than of brick with mortar, and consequently too elastic not to settle to a large extent in the course of erection. Hence is it that no measurements of a Byzantine structure, even on the ground floor, are accurate within more than 5 cm., while above the ground they vary to a much greater degree, rendering minute measurements quite valueless.

Lastly, as the marble panelling was fitted after the completion of the body of the building, it had to be adapted to any divergence that had previously occurred in the settling of the walls or the spreading of the vaults. The marble panelling, it should also be observed, is here cut to the diagonal at one angle, and not at the other.

Apart from the set back of the masonry at the middle string-course, this church, therefore, supplies no evidence for an intentional widening of the structure from the ground upwards. Any further widening than that at the middle string-course was accidental, due to the nature of the materials employed, not to the device of the builder, and was allowed by the architect because unavoidable. Such irregularities are inherent in the Byzantine methods of building.

LOCATION SATELLITE MAP

These scripts and photographs are registered under © Copyright 2018, respected writers and photographers from the internet. All Rights Reserved.