Fatih - Istanbul - Turkey

GPS : 41°00'53.9"N 28°56'37.6"E / 41.014972, 28.943778

PHOTOGRAPHS ALBUM

PHOTOGRAPHS ALBUM

The complex is located in the Fatih district of Istanbul, Turkey, along the Adnan Menderes (formerly Vatan) Caddesi (Avenue), in a modern context. Fenari İsa Mosque (full name in Turkish: Molla Fenari İsa Camii), in Byzantine times known as the Lips Monastery, is a mosque in Istanbul, made of two former Eastern Orthodox churches. The complex is located in the Fatih district of Istanbul, Turkey, along the Adnan Menderes (formerly Vatan) Caddesi (Avenue), in a modern context.

In year 908 the Byzantine Admiral Konstantinos Lips, who would perish in 917 fighting against Simeon I's Bulgaria, inaugurated at the presence of the Emperor Leo VI the Wise a nunnery dedicated to the Virgin Theotokos "Immaculate Mother of God" in a place called "Merdosangaris", in the valley of the Lykos. The monastery, which had also a Xenon "hospital" with 15 beds attached, was known also after his name (Mone tou Livos), and became one of the largest of Constantinople.

The church was built on the remains of another shrine from the 6th century, and used the tombstones of an ancient Roman cemetery. Relics of Saint Irene were stored here. The church of the monastery, also dedicated to the Virgin, was built on the remains of another shrine of the sixth century, and using the tombstones of an ancient roman cemetery. The church hosted the relics of Saint Irene, and the monastery, according to its Typicon, hosted a total of 50 women. The church was generally known as "North Church".

After the Latin invasion and the restoration of the Byzantine Empire, between 1286 and 1304, Empress Theodora, widow of Emperor Michael VIII Palaiologos (r. 1259-1282), erected another church dedicated to St. John the Baptist south of the first church. Several exponents of the imperial dynasty of the Palaiologos were buried there besides Theodora: her son Constantine, Empress Irene of Montferrat and her husband Emperor Andronikos II (r. 1282-1328).

This church is generally known as the "South Church". The Empress restored also the nunnery, which by that time had been possibly abandoned. According to its typikon, the nunnery at that time hosted a total of 50 women and also a Xenon for laywomen with 15 beds attached.

During the 14th century an esonarthex and a parekklesion were added to the church. The custom of burying members of the imperial family in the complex continued in the 15th century with Anna, first wife of Emperor John VIII Palaiologos (r. 1425-1448), in 1417. The church was possibly used as a cemetery also after 1453.

In 1497-1498, shortly after the Fall of Constantinople and during the reign of Sultan Beyazid II (1481-1512), the south church was converted into a mescit (a small mosque) in 1496 by the Ottoman dignitary Fenarizade Alaeddin Ali ben Yusuf Effendi, Kadıasker of Rumeli, and nephew of Molla Şemseddin Fenari, whose family belonged to the religious class of the ulema. He built a minaret in the southeast angle, and a mihrab in the apse. Since one of the head preachers of the madrasah was named Isa ("Jesus" in Arabic and Turkish), his name was added to that of the mosque.

During the reign of Sultan Murat IV, Sheikh Ise’l Mahvi transformed the northern church into a zawiya. The domes and pulleys of the masjid, converted into a mosque in 1650, were rebuilt in 1830. The structure, abandoned after the fire of 1918, has continued to serve as a mosque following restoration work between 1960 and 1963.

The edifice burned down in 1633, was restored in 1636 by Grand Vizier Bayram Pasha, who upgraded the building to cami (mosque) and converted the north church into a tekke (a dervish lodge). In this occasion the columns of the north church were substituted with piers, the two domes were renovated, and the mosaic decoration was removed.

After another fire in 1782, the complex was restored again in 1847/48. In this occasion also the columns of the south church were substituted with piers, and the balustrade parapets of the narthex were removed too. The building burned once more in 1918, and was abandoned. During excavations performed in 1929, twenty-two sarcophagi have been found. The complex has been thoroughly restored between the 1970s and 1980s by the Byzantine Society of America, and since then serves again as a mosque.

The north church has an unusual quincuncial (cross-in-square) plan, and was one of the first shrines in Constantinople to adopt this plan, whose prototype is possibly the Nea Ekklesia (New Church), erected in Constantinople in the year 880, of which no remains are extant. The dimensions of the north church are small: the naos is 13 meters long and 9.5 meters wide, and was sized according to the population living in the monastery at that time.

The masonry of the northern church was erected by alternating courses of bricks and small rough stone blocks. In this technique, which is typical of the Byzantine architecture of the 10th century, the bricks sink in a thick bed of mortar. This edifice has three high apses: the central one is polygonal, and is flanked by the other two, which served as pastophoria, prothesis and diakonikon. The apses are interrupted by triple and single lancet windows.

The walls of the central arms of the naos cross have two orders of windows: the lower order has triple lancet windows, the higher semicircular windows. Two long parekklesia, each one ended by a low apse, flanks the presbytery of the naos. The angular and central bays are very slender. At the four edges of the building are four small roof chapels, each surmounted by a cupola.

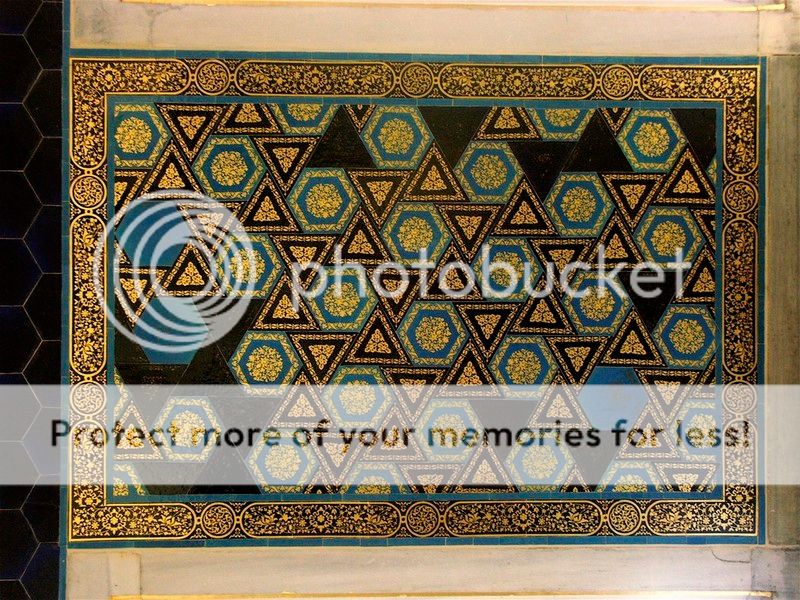

The remainders of the original decoration of this church are the bases of three of the four columns of the central bay, and many original decorating elements, which survive on the pillars of the windows and on the frame of the dome. The decoration consisted originally in marble panels and coloured tiles: the vaults were decorated with mosaic. Only spurs of it are now visible. As a whole, the north church presents strong analogies with the Bodrum Mosque (the church of Myrelaion).

The south church is a square room surmounted by a dome, and surrounded by two deambulatoria, an esonarthex and a parekklesion (added later). The north deambulatorium is the south parekklesion of the north church. This multiplication of spaces around the central part of the church is typical of the late Palaiologian architecture: the reason of that was the need for more space for tombs, monuments erected to benefactors of the church, etc. The central room is divided from the aisles by a triple arcade.

During the mass the believers were confined in the deambulatoria, which were shallow and dark, and could barely see what happened in the central part of the church. The masonry is composed of alternated courses of bricks and stone, typical of the late Byzantine architecture in Constantinople. The lush decoration of the south and of the main apses (the latter is heptagonal), is made of a triple order of niches, the middle order being alternated with triple windows.

The bricks are arranged to form patterns like arches, hooks, Greek frets, sun crosses, swastikas and fans. Between these patterns are white and dark red bands, alternating one course of stone with two to five of bricks. This is the first appearance of this most important decorating aspect of the Palaiologian architecture in Constantinople. The church has an exonarthex surmounted by a gallery, which was extended to reach also the north church.

The parekklesion was erected alongside the southern side of the south church, and was connected with the esonarthex, so that the room surrounds the whole complex on the west and south side. Several marble sarcophagi are placed within it. As a whole, this complex represents a notable example of the middle and late Byzantine Architecture in Constantinople.

Of the decoration of this church remain the bases of three of the four columns of the central bay, and many original decorating elements, which survive on the pillars of the windows and on the frame of the dome. The decoration consisted originally in marble panels and coloured tiles: the vaults were decorated with mosaics. Only spurs of it are now visible. As a whole, the north church presents strong analogies with the Bodrum Mosque (the church of Myrelaion).

The building comprises two churches, which, while differing in date and type, stand side by side, and communicate with each other through an archway in their common wall, and through a passage in the common wall of their narthexes. As if to keep the two churches more closely together, they are bound by an exonarthex, which, after running along their western front, returns eastwards along the southern wall of the south church as a closed cloister or gallery.

The North Church is of the normal four column type. The four columns which originally supported the dome were, however, removed when the building was converted into a mosque in Turkish times, and have been replaced by two large pointed arches which span the entire length of the church. But the old wall arches of the dome-columns are still visible as arched piercings in the spandrils of the Turkish arches. A similar Turkish 'improvement' in the substitution of an arch for the original pair of columns is found in the north side of the parecclesion attached to the Pammakaristos.

The dome with its eight windows is likewise Turkish. The windows are lintelled and the cornice is of the typical Turkish form. The bema is almost square and is covered by a barrel vault formed by a prolongation of the eastern dome arch; the apse is lighted by a lofty triple window. By what is an exceptional arrangement, the lateral chapels are as lofty both on the interior and on the exterior as is the central apse, but they are entered by low doors.

In the normal arrangement, as, for instance, in the Myrelaion, the lateral chapels are low and are entered by vaults rising to the same height as those of the angle chambers, between which the central apse rises higher both externally and internally. The chapels have niches arched above the cornice on three sides, and are covered by cross-groined vaults which combine with the semicircular heads of the niches to produce a very beautiful effect. To the east they have long bema arches flanked by two small semicircular niches, and are lighted by small single windows.

The church is preceded by a narthex in three bays covered by cross-groined vaults supported on strong transverse arches. At either end it terminates in a large semicircular niche. The northern one is intact, but of the southern niche only the arched head remains. The lower part of the niche has been cut away to afford access to the narthex of the south church. This would suggest that, at least, the narthex of the south church is of later date than the north church. Considered as a whole the north church is a good example of its type, lofty and delicate in its proportions.

The South Church narthex is unsymmetrical to the church and in its present form must be the result of extensive alteration. It is in two very dissimilar bays. That to the north is covered with a cross-groined vault of lath and plaster, probably on the model of an original vault constructed of brick. A door in the eastern wall leads to the north aisle of the church. The southern bay is separated from its companion by a broad arch. It is an oblong chamber reduced to a figure approaching a square by throwing broad arches across its ends and setting back the wall arches from the cornice.

This arrangement allows the bay to be covered by a low drumless dome. Two openings, separated by a pier, lead respectively to the nave and the southern aisle of the church. The interior of the church has undergone serious alterations since it has become a mosque, but enough of the original building has survived to show that the plan was that of an 'ambulatory church.

Each side of the ambulatory is divided into three bays, covered with cross-groined vaults whose springings to the central area correspond exactly to the columns of such an arcade as that which occupies the west dome bay of S. Andrew. We may therefore safely assume that triple arcades originally separated the ambulatory from the central area and filled in the lower part of the dome arches. The tympana of these arches above were pierced to north, south, and west by three windows now built up but whose outlines are still visible beneath the whitewash which has been daubed over them. The angles of the ambulatory are covered by cross vaults.

The pointed arches at present opening from the ambulatory to the central area were formed to make the church more suitable for Moslem worship, as were those of the north church. In fact we have here a repetition of the treatment of the Pammakaristos, when converted into a mosque. The use of cross-groined vaults in the ambulatory is a feature which distinguishes this church from the other ambulatory churches of Constantinople and connects it more closely with the domed-cross church. The vaults in the northern portion of the ambulatory have been partially defaced in the course of Turkish repairs.

The central apse is lighted by a large triple window. It is covered by a cross-groined vault and has on each side a tall shallow segmental niche whose head rises above the springing cornice. Below this the niches have been much hacked away. The passages leading to the lateral chapels are remarkably low, not more than 1.90 m high to the crown of the arch.

The southern chapel is similar to the central apse, and is lighted by a large triple window. The northern chapel is very different. It is much broader; broader indeed than the ambulatory which leads to it, and is covered by barrel vaults. The niches in the bema only rise to a short distance above the floor, not, as on the opposite side, to above the cornice. It is lighted by a large triple window similar to those of the other two apses.

The outer narthex on the west of the two churches and the gallery on the south of the south church are covered with cross-groined vaults without transverse arches. The wall of the south church, which shows in the south gallery, formed the original external wall of the building. It is divided into bays with arches in two and three orders of brick reveals, and with shallow niches on the broader piers.

The exterior of the two churches is very plain. On the west are shallow wall arcades in one order, on the south similar arcades in two orders. The northern side is inaccessible owing to the Turkish houses built against it. On the east all the apses project boldly. The central apse of the south church has seven sides and shows the remains of a decoration of niches in two stories similar to that of the Pantokrator; the other apses present three sides. The carved work on the window shafts is throughout good.

An inscription commemorating the erection of the northern church is cut on a marble string-course which, when complete, ran across the whole eastern end, following the projecting sides of the apses. The letters are sunk and marked with drill holes. Wulff is of opinion that the letters were originally filled in with lead, and, from the evidence of this lead infilling, dates the church as late as the fifteenth century.

But it is equally possible that the letters were marked out by drill holes which were then connected with the chisel, and that the carver, pleased by the effect given by the sharp points of shadow in the drill holes, deliberately left them. The grooves do not seem suitable for retaining lead. In the course of their history both churches were altered, even in Byzantine days. The south church is the earlier structure, but shows signs of several rebuildings.

The irregular narthex and unsymmetrical eastern side chapels are evidently not parts of an original design. In the wall between the two churches there are indications which appear to show the character of these alterations and the order in which the different buildings were erected. As has already been pointed out, the north side of the ambulatory in the south church, which for two-thirds of its length is of practically the same width as the southern and western sides, suddenly widens out at the eastern end and opens into a side chapel broader than that on the opposite side.

The two large piers separating the ambulatory from the central part of the north church are evidently formed by building the wall of one church against the pre-existing wall of the other. The easternmost pier is smaller and, as can be seen from the plan, is a continuation of the wall of the north church. Clearly the north church was already built when the north-eastern chapel of the south church was erected, and the existing wall was utilised. As the external architectural style of the three apses of the south church is identical, it is reasonable to conclude that this part of the south church also is later in date than the north church.

For if the entire south church had been built at the same time as the apses, we should expect to find the lateral chapels similar. But they are not. The vaulting of the central apse and of the southern lateral chapel are similar, while that of the northern chapel is different. On the same supposition we should also expect to find a similar use of the wall of the north church throughout, but we have seen that two piers representing the old wall of the south church still remain. The narthex of the south church, however, is carried up to the line of the north church wall.

The four column type is not found previous to the tenth century. The date of the north church was originally given on the inscription, but is now obliterated. Kondakoff dates it in the eleventh or twelfth century. Wulff would put it as late as the fifteenth. But if the view that this church was attached to the monastery of Lips is correct, the building must belong to the tenth century.

The ambulatory type appears to be early, and the examples in Constantinople seem to date from the sixth to the ninth century. It may therefore be concluded that, unless there is proof to the contrary, the south church is the earlier. In that case the southernmost parts of the two large piers which separate the two churches represent the old outer wall of the original south church, whose eastern chapels were then symmetrical.

To this the north church was added, but at some subsequent date the apses of the south church demanded repair and when they were rebuilt, the north-eastern chapel was enlarged by the cutting away of the old outer wall. To this period also belongs the present inner narthex. The fact that the head of the terminal niche at the south end of the north narthex remains above the communicating door shows that the south narthex is later. The outer narthex and south gallery are a still later addition.

LOCATION SATELLITE MAP

These scripts and photographs are registered under © Copyright 2018, respected writers and photographers from the internet. All Rights Reserved.